How the Victorians Changed Christmas by Anna Mazzola

Hate Christmas? Blame the Victorians. At the beginning of the 19th century, Christmas was barely celebrated. It wasn’t just Ebenezer Scrooge who begrudged his clerk the day off – many didn’t consider the 25th December to be a holiday. There were no crackers, no cards, no Santa, and no Christmas trees, at least not in England. By mid-century, however, Christmas was big business.

Charles Dickens himself was partly to blame. A Christmas Carol, published in 1843, helped to popularise among the newly-enriched middle classes the idea that the day was all about plum pudding, presents, parlour games and family. Dickens can’t be held personally responsible for the Christmas carols, however – that was a tradition that had been lurking around for a long time, but which the Victorians took it upon themselves to revive.

Also on the naughty list is Henry Cole, who in 1843 commissioned an artist to design a Christmas card and then printed off a thousand copies to sell in his art shop in London. At one shilling each, they were too expensive for most people, but as the costs of card production and postage dropped, the idea gathered momentum so that by 1880 the Christmas card industry produced 11.5 million cards in that year alone. Many of the designs are delightfully peculiar, featuring waltzing beetles, dueling frogs and, for some reason, mice riding lobsters.

My personal animosity is saved for British confectioner Tom Smith. In 1848 he was inspired by French bon-bon sellers to invent a new way to sell his wares: ‘firecracker sweets’. He covered the sweets in paper treated with chemicals so that they made a small explosion when pulled apart. Later in the Victorian period, the sweets were replaced by small presents. Now, of course, they’re full of plastic bits of tat, terrible jokes, and paper hats that we’re forced to wear throughout dinner.

Then there’s the Christmas tree dropping needles all over your carpet. Early in the century, people decked the halls (and windows) with mistletoe and ivy, but in the 1830s, German families living in Manchester began to put up Christmas trees in their houses and in 1848 the Illustrated London News published an illustration of Queen Victoria, Albert and their children grouped around a Christmas tree. By 1860, every well-to-do family in the land was dragging a tree into their parlour and decorating it with candles, sweets, fruit, and hand-made gifts. As present-giving became more central to Christmas, and the gifts became larger and more expensive, they moved under the tree.

It wasn’t all commercialism: charity played a big part. Newspapers printed appeals for donations for the sick and the poor, and the rich of the countryside were expected to donate winter fuel to their villagers. Charitable organisations provided Christmas dinners for paupers, and even the convicts languishing in England’s prisons were served some form of Christmas lunch.

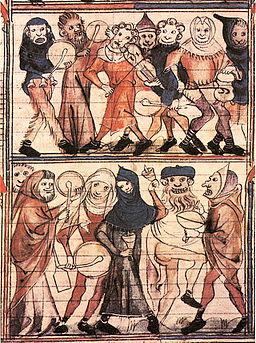

People had been feasting at Christmas since before the Middle Ages, but it was during the Victorian period that the ‘traditional Christmas dinner’ of turkey and plum-pudding took shape. Early Victorian mince pies were made from meat, but over the course of the century meat-free recipes gained popularity and they became the sweet pies we gorge ourselves on in December. At the beginning of the era, beef or goose tended to be centrepiece. Turkeys were too expensive, as they had to be herded to market wearing little leather boots to protect their feet, and then fattened up after their journey. With the arrival of trains, however, the price of turkeys dropped, and they were voted in as the favourite Christmas dinner.

The Victorians also saddled us with Santa, who was an amalgam of the green-clad ‘Old Christmas’ and St. Nicholas, or Sinter Klass, who had travelled via Dutch settlers to the USA in the 17th Century. By the 1870s, Sinter Klass had melded with Old Christmas to become Father Christmas, complete with red robes, reindeer and sleigh. Christmas was now firmly about children, family, presents and money. Bah Humbug!

Anna Mazzola is the author of THE UNSEEING