The Conqueror’s Christmas by David Churchill

Two great empire builders were crowned on Christmas Day. The first, in the year 800, was Charlemagne. He liked to claim that it had happened by accident. He’d popped into St Peter’s Basilica in Rome for Christmas Mass, knelt down at the altar to pray and the next thing he knew, Pope Leo II was placing the crown of the Roman Empire on his head and calling him Emperor.

It seems less than entirely credible that one of the greatest rulers in all European history could have received his mightiest title like an unwary shopper who wanders past a department store cosmetics counter and is suddenly sprayed with scent by an overactive saleswoman. Still, there was nothing remotely accidental about the second Christmas coronation.

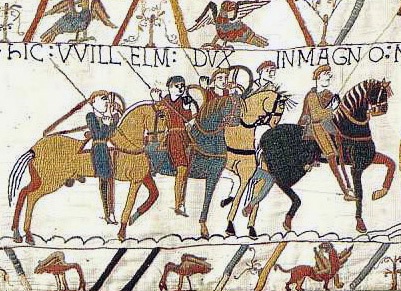

William of Normandy – known to his contemporaries as William the Bastard (on account of being the illegitimate offspring of a couple of unmarried teenage lovers, one of whom happened to be the second son of Duke Richard II of Normandy), but now more commonly called the Conqueror – absolutely knew what he was doing when he had himself crowned King of England on 25 December 1066.

William was a fascinating combination of ruthless, sometimes brutal, warrior and surprisingly subtle, calculating politician. Sometimes he was both at the same time. There was nothing William liked better than to use a single act of truly shocking violence to create such terror in his enemies as to render any further unpleasantness unnecessary.

By the time he arrived in London in December 1066, he had defeated and killed King Harold of England at Hastings after a day of brutal, hand-to-hand savagery. He’d taken effective control of southern England from Winchester in the west across to the Kent coast in the east. He’d cut a swathe of devastation that had encircled London and persuaded a large number of English nobles that further resistance was futile. Now their best bet was to accept him as their monarch and hope that he would treat them well.

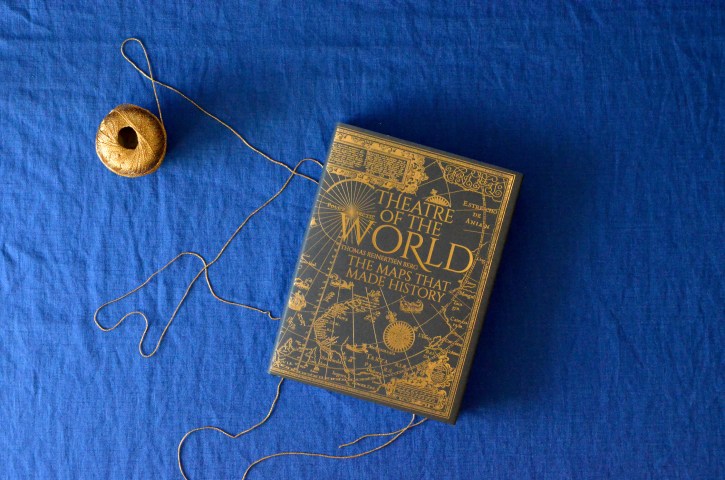

The venue William specifically chose for the coronation ceremony was the newly rebuilt church of St Peter’s Abbey. It stood beside the royal Palace of Westminster on Thorney Island, beside the River Thames a little way upstream from London itself.

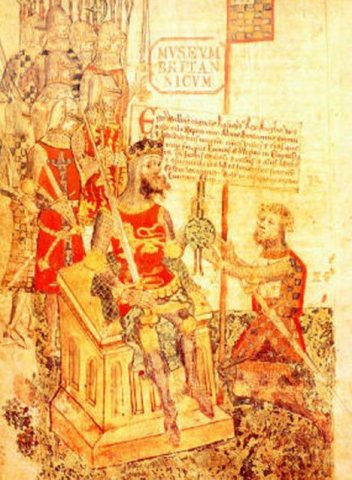

This church, which we now know as Westminster Abbey, had been the pet project of King Edward the Confessor. He had died just days after seeing the building consecrated almost exactly one year earlier and been laid to rest within its walls. So, by accepting the crown of England in the same place, William was very deliberately placing himself in the due line of succession from Edward. He underlined this by having Aldred, Archbishop of York, preside over a ceremony, spoken in English, that was in large part the same as that by which English kings had been crowned for the past century or more.

William’s claim to the throne rested on the hotly disputed assertion that Edward had made him his heir, and the indisputable fact that he had been related by blood to the childless king: Edward’s mother had been William’s great-aunt Emma of Normandy. For psychological as well as political reasons, issues of legitimacy were hugely important to William. It was not enough that he had seized the throne by force or arms. He wanted everyone to know that he had a right to be there.

But, at the same time, he was also keen to remind them that he was, in fact, their conqueror. So the ceremony was not only in English, but also Norman … or rather, it was Frankish, in a very clear nod to the traditions of Charlemagne.

This second strand of the ceremony was presided over, in French, by Geoffrey, Bishop of Coutances, in Normandy. This ceremony contained a series of acclamations known as the ‘Laudes Regiae’ or royal praises which had been sung at the coronation of Charlemagne. They saluted, ‘The most serene William, the great and peace-giving king, crowned by God, life and victory.’

‘The most serene’ or in Latin ‘serenissimus’ is a phrase that related directly to Charlemagne, who – having decided that he was actually rather happy to be the Holy Roman Emperor – referred to himself as ‘Karolus serenissimus Augustus a Deo coronatus magnus pacificus imperator Romanum gubernans imperium’, or ‘Charles, most serene Augustus crowned by God, the great, peaceful emperor ruling the Roman empire.’

The political subtexts of the whole affair were rather undermined by another French tradition in which the priest asked the congregation if they accepted their new monarch as their ruler and they all shouted their assent. The noise they made was heard by the Norman troops massed outside the church, who thought that the English barons were actually shouting in defiance against William. The Normans reacted to this threat as they did to any other: with immediate, savage violence and destruction.

The mayhem spread into the cathedral itself, but William did not let it distract him. He insisted that the whole complicated double-ceremony should be performed to the bitter end. He knew that his status as undisputed king mattered far more in the long term than any temporary unrest.

And so, on Christmas Day, William gave himself England as a very special gift. And he gave England a ceremony that made it at once a unique, distinctive island kingdom and a part of a wider European tradition. Up in the North, however, revolt was brewing. There were still plenty of English barons who had no desire to see a foreign interloper rule their nation.

Precisely 950 years have passed since then and one might, at this first post-Brexit Christmas, observe that nothing much has changed. The question of England’s status relative to Europe remains unsettled. We still argue about the degree to which we will accept continental influence upon our domestic affairs.

But let’s not get into that. Why wreck another English Christmas?

David Churchill is the author of DEVIL and DUKE