Historical fiction, ancestry and artefacts

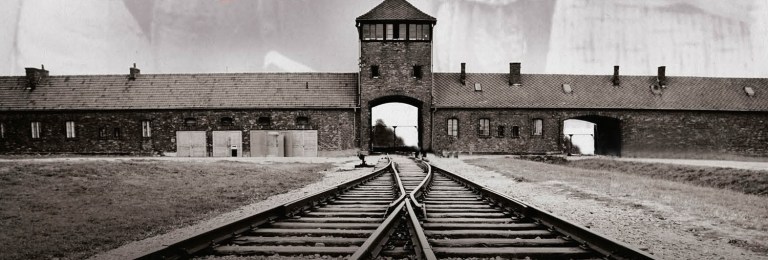

My most recent novel, TESTAMENT, contains five chapters of historical fiction – a prologue set at the time of the Phoenicians in the 6th century BC, two chapters set during the British Abyssinia campaign of 1868-9 and another two chapters at Bletchley Park in 1943. That emphasis on historical fiction continues the pattern of my eight previous Jack Howard novels, all present-day thrillers but with settings ranging from the earliest seafaring in the Neolithic to the Roman destruction of Jerusalem and the final days of the Nazis at the end of the Second World War. One of my novels, PHARAOH, is really a historical novel within a novel, with more than half of the book devoted to an adventure in which a British officer and his Canadian voyageur companion seek out General Gordon in Khartoum in 1885, leaving clues to an extraordinary ancient discovery that Jack Howard follows into the next novel PYRAMID. That story, like the Abyssinia account in TESTAMENT and settings in 19th century India and Afghanistan in THE TIGER WARRIOR, reflects a long-standing fascination with military and colonial history – including North American history – drawn from my own family background. As well as the Jack Howard series, I’ve written two entire novels of historical fiction, DESTROY CARTHAGE and THE SWORD OF ATTILA, both set during the Roman period.

As a result of this, although I’m classed mainly as an author of present-day adventure thrillers, almost half of my published word count has been historical fiction, and that describes my passion as an author as much as the present-day adventures that I’ve created on the basis of my experiences as a diver and an archaeologist. Two factors underlie much of the historical fiction in my novels. The first is the fascination with my own ancestors, and the insight that has given me into seafaring, military and colonial history. Genealogy can be a great basis for historical fiction because you are chasing characters, not events – and because the biographical details are usually sparse, much time is spent speculating on the nature of characters and their byways through history. The second factor is artefacts, something I’ve been passionate about since childhood; a sherd of pottery, a coin, or perhaps a Victorian medal, can transport me into the past with the same intensity and desire to see the fuller picture that I can get by pursuing the life of an ancestor.

I first went to Bletchley when I was writing THE LAST GOSPEL, and researching a great-great uncle who is the basis for a character in that novel – a Cambridge mathematician who had worked as a codebreaker for the predecessor of Bletchley in the First World War. I went again when I was beginning to think about TESTAMENT and had been immersed in another strand of family history, researching the convoy battles that my grandfather had experienced as a Merchant Navy officer during the Second World War. I’d been to the National Archives researching a particularly grim convoy battle off West Africa and the sinking of one of my grandfather’s sister-ships, Clan Macpherson, a story that I wanted to weave into the novel. At Bletchley, I realised that the historical context I wanted was the Park itself, the nerve centre for convoy operations during the war. For me, the story was rendered more vivid by holding the actual handwritten reports by the captain on the sinking, as well as by a recent experience diving on a torpedoed merchantman that I wanted to be the basis for a fictional dive on the Clan Macpherson.

Sitting in Hut 8 behind the desk in Alan Turing’s reconstructed office, I also reflected on the strictures in British society that defined the type of people who worked at Bletchley during the war. We’re used to the idea that class and educational background were dispensed with in the search for the brightest minds, but in truth a large segment of society was excluded – those who had never had the opportunity even to go to grammar school. I thought of my own maternal grandmother, the daughter of a Shropshire miner, a bright girl who had yearned for more education but had to leave school at the age of 14 to go into domestic service, and would have loved to be involved with the type of work that women were doing at Bletchley. In my novel, I based my main character at Bletchley on the contribution that women such as my grandmother could have made to the war effort had they enjoyed the educational opportunities of succeeding generations; she is the one who has the insight into the true purpose of Clan Macpherson and its precious cargo.

In TESTAMENT, the wreck of the Clan Macpherson provides Jack with a clue to one of the greatest lost treasures of antiquity, and leads him to the Abyssinia expedition of 1867-8. I’d always been fascinated by that expedition – by its grandeur and its folly, and by its larger-than life protagonist King Theodore, whose kidnapping of missionaries had provoked the British response, and who eventually killed himself in his mountain stronghold of Magdala with a pistol that had been sent to him as a present by Queen Victoria. The date of the expedition, as well as the fact that it was sent from India, allowed me to weave into the story characters from previous novels, including Sapper Jones – who appears in THE TIGER WARRIOR and PHARAOH – and Jack’s ancestor Lieutenant Howard of the Madras Sappers and Miners, a character based on one of my own ancestors who we first meet in a jungle rebellion in India in THE TIGER WARRIOR.

The monumental struggle to reach Magdala, by the British expedition on the one hand, inching its way up from the coast, and by the increasingly deranged Theodore on the other, dragging his huge bronze mortar Sevastopol up the mountain tracks at the cost of countless lives, seemed an analogue of the most arduous archaeological expeditions of discovery, with Magdala itself almost as spectral as an El Dorado or a Shangri-La. In truth, it was a very real place of treasure; the British Museum even sent along a representative to secure as much of the loot as possible. What crystalized the story for me was the artefacts of that expedition – the remains that still exist on the plateau of Magdala, including the giant bronze mortar, as well as the works of art and literature that you can see in the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum and other collections to this day.

I have an archaeologist’s belief that the most compelling view of history often comes through artefacts, and through the stimulus to the imagination that comes from the process of discovery. I always have artefacts with me when I’m writing my novels. I’m currently researching a story set during the First World War, and have just returned from a trip to study the archaeology of the Somme region in France, tracing the experiences of my other grandfather. One of the artefacts I picked up was a rusted piece of shrapnel from a place where he survived being blown up by a shell while all around him were killed and wounded. That in itself gives the artefact particular poignancy for me – had that shell burst slightly differently I might not be here today.

Holding that piece of shrapnel now, feeling its sharp edges, smelling it, gives those events of a hundred years ago an immediacy not possible in any other way, just as the artefacts I’ve discovered in shipwrecks – from ancient pottery to silver pieces-of-eight from the Spanish Main – provide vivid portholes into the past. For me, ancestry and archaeology are at the core of my historical fiction, and will be the basis for many novels to come.

David Gibbins’ latest novel TESTAMENT is out NOW

www.facebook.com/DavidGibbinsAuthor