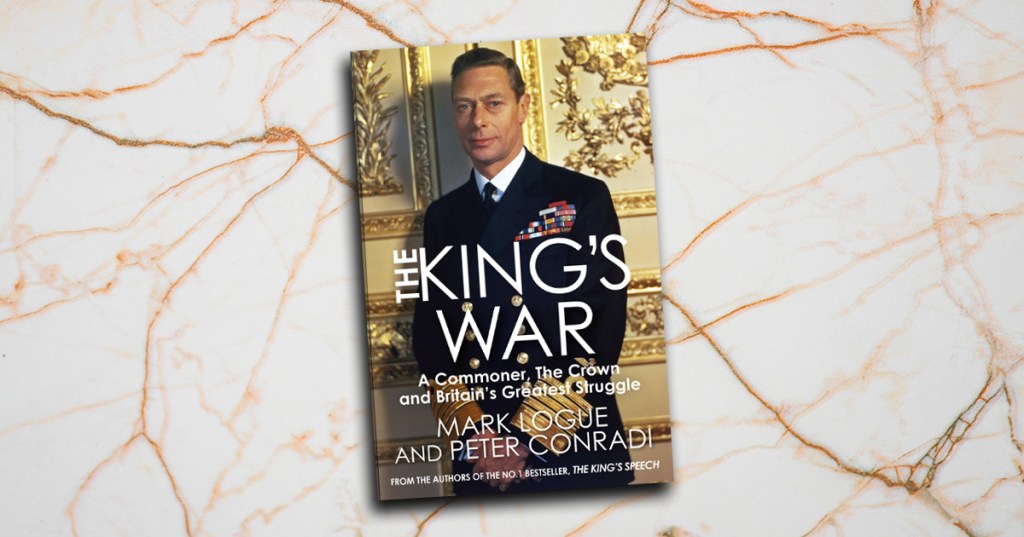

The King’s War by Mark Logue and Peter Conradi

Victory!

It’s two weeks until publication day for The King’s War, by Mark Logue and Peter Conradi, an incredible insight into the monarchy during the darkest days of WWII. The King’s War draws on diaries, letters and other documents left by George VI’s speech therapist, Lionel Logue, and his wife, Myrtle. It provides a fascinating portrait of two men and their respective families – the Windsors and the Logues – as they together faced up to the greatest challenge in Britain’s history.

VE Day dawned fine and warm after heavy thunderstorms overnight. That morning Logue received another message from the Palace. ‘The King would like to see you at dinner tonight, and bring Mrs Logue’ – to which an unidentified hand had added: ‘Tell her to wear something bright’. When Lionel and Myrtle set off for Buckingham Palace at 6.30, they found the streets decked with flags but virtually deserted. It took them only a few minutes to drive the seven miles from Beechgrove to the centre of London. They encountered their first traffic barrier near Victoria Station, but Miéville had rung up Forest Hill police and asked them to organize a pass, which Logue had picked up. This got them through the barrier and on to the first gate of the Palace. Logue expected a hold-up, but the policeman there was an old friend and the gate swung open. As their car crossed the courtyard towards the Privy Purse entrance, a tremendous cheer broke out – the King and Queen had just come out onto the balcony again. Lionel and Myrtle joined other members of the royal household in wildly cheering and waving handkerchiefs.

Lionel made for the new broadcasting room on the ground floor, facing the lawn, and went through the speech with the King. They made a couple of minor alterations before the King declared, rather plaintively: ‘If I don’t get dinner before 9 I won’t get any after, as everyone will be away, watching the sights.’ This, coming from a man in such an exalted position, sent Logue into paroxysms of laughter – so much that the King himself joined in, though after reflecting for a moment, he said: ‘It’s funny, but it is quite true.’

After they had eaten, they went back to the broadcasting room at 8.35. Wood, of the BBC, was there. He and Logue synchronized their watches and had another run-through. There were two minutes to go before the King, dressed in his naval uniform, was due to step out once more onto the balcony, but this time to make a speech. Another small further alteration, and then the Queen, now wearing a white ermine wrap over her evening gown and a diamond tiara in her hair, came into the room, as she always did, to wish her husband luck.

Once the floodlights were switched on, a mighty roar erupted from the crowd. ‘And in an instant the sombre scene has become fairyland – with the Royal Ensign, lit from beneath, floating in the air,’ Logue wrote in his diary. ‘Another roar – the King and Queen come on to the balcony.’ He was struck by the way the lights played on the Queen’s tiara; as she turned, smiling, to wave to the crowd, the floodlights created what looked like a band of flame around her head.

‘Today we give thanks to Almighty God for a great deliverance,’ the King declared:

Speaking from our Empire’s oldest capital city, war-battered but never for one moment daunted or dismayed, speaking from London, I ask you to join with me in that act of thanksgiving.

Germany, the enemy who drove all Europe into war, has been finally overcome. In the Far East we have yet to deal with the Japanese, a determined and cruel foe. To this we shall turn with the utmost resolve and with all our resources But at this hour when the dreadful shadow of war has passed far from our hearths and homes in these islands, we may at last make one pause for thanksgiving and then turn our thoughts to the task all over the world which peace in Europe brings with it.

Continuing, the King saluted those who had contributed to victory – both alive and dead – and reflected on how the ‘enslaved and isolated peoples of Europe’ had looked to Britain during the darkest days of the conflict. He also turned to the future, urging that his subjects should ‘resolve as a people to do nothing unworthy of those who died for us and to make the world such a world as they would have desired, for their children and for ours.’

‘We may allow ourselves a brief period of rejoicing,’ he concluded. ‘But let us not forget for a moment the toil and efforts that lie ahead. Japan with all her treachery and greed, remains unsubdued.’

The King was exhausted – and it showed; he spoke slowly and stumbled more than usual over his words, but that didn’t seem to matter. The crowd listened in silence, but at the end they raised a great cheer and sang the national anthem. ‘We all roared ourselves hoarse,’ recalled Noël Coward, who was among the crowd. ‘I suppose this is the greatest day in our history.’

The King and Queen reappeared on the balcony together with the princesses at about 10.45 p.m., standing waving to the crowd for about ten minutes, and yet again just before midnight as searchlights flashed across the sky. This time, though, the two princesses were not with them. They had asked their parents to be allowed out to join in the celebrations. The King agreed: ‘Poor darlings, they have never had any fun yet,’ he wrote in his diary. And so, Elizabeth and Margaret slipped out of the Palace incognito, chaperoned by their uncle, David Bowes-Lyon, the Queen’s youngest brother, and accompanied by their governess and a party of young officers. No one recognized the nineteen-year-old heir to the throne and her fourteen-year-old sister as they joined the conga line into one door of the Ritz and out of the other amid crowds that chanted ‘We want the King! We want the Queen!’ and sang ‘Land of Hope and Glory’.

Years later the future Queen was to describe this as one of the most memorable nights of her life.