1066: What If…? – David Churchill

In a poll of more than two thousand people taken in January 2016, to mark the 950th anniversary of the Norman Conquest, 1066 was named as the most memorable date in British history. England had already been a coherent kingdom for more than a century before the Battle of Hastings. Yet 1066 is the point at which we still think of the country, as we know it, being born.

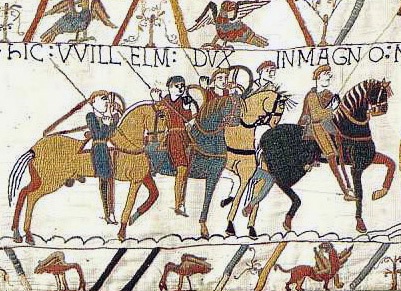

But what if the English had beaten the Normans and thus not been conquered at all? The Battle of Hastings was a desperately hard-fought contest. Any number of factors might have changed the outcome. For example, suppose King Harold’s disaffected brother Tostig had not prompted Harald Hardrada, King of Norway, into invading England. Hardrada arrived in Yorkshire from the north a few weeks before William turned up in Sussex from the south. Harold had to march his army all the way to one end of his kingdom and win the Battle of Stamford Bridge, before turning round and trudging back, severely depleted, to face the Normans. If he’d only had one enemy to fight, chances are he would not have been defeated.

Even then, if Harold had just waited a few more days, bottling up William’s army close to the coast while thousands of fresh soldiers reinforced the English army, the odds would have been hugely in his favour. Then we would talk about William the Loser and Harold would be the conquering hero.

It was not as if eleventh-century England lacked good soldiers. Stamford Bridge proved that. Nor did 1066 resemble the Roman invasions of 55BC and 43AD: a far more civilised, powerful empire invading a relatively backward, disorganised territory. Anglo-Saxon England was arguably the most coherent, well-organised kingdom in Europe. It possessed a prosperous economy. English craftsmen and needlewomen were much admired. And they lived in relative peace. In 1066, Normandy was littered with castles. Its dukes and lesser nobles spent fortunes building them to fend off their rivals within Normandy or their enemies without. The nobles of England did not waste their resources on fortifications. They didn’t have to. Yes, there were conflicts on the fringes: notably the Welsh marches and the Scottish borders. But by 1066, the heartland of England had known fifty years of relative peace and prosperity, certainly when compared to eleventh-century Normandy. If William had not turned up in 1066 that would have continued … until someone else invaded, that is. After all, England was such a ripe fruit that someone was bound to want to pick it.

But let’s make another supposition. Let’s say the English withstood all-comers. Imagine they entered the Middle Ages as an even-happier breed of men and women living on their sceptred isle. What then?

Without the Normans, and the ties of blood and land to continental Europe that they brought with them, the English would have remained more insular. They might have expanded into the whole of Great Britain and Ireland. But they would not have been embroiled in a Hundred Years War, for their kings would have had no claims to France to advance or defend.

On the other hand the English language – arguably our single greatest cultural contribution to the world – would have been a far less noble thing without William’s intervention. English possesses an incredible richness of vocabulary. We often have two words covering the same idea from different linguistic angles, for example ‘chair (as in the French word chaise) and ‘stool’ (as in the German Stuhl). That’s because the Normans made French the language of England’s royal court, thereby adding a shot of Romance to the Germanic roots of Old English. Without William the Conqueror, we might not have had that other William, Shakespeare to give us phrases like ‘sceptred isle’ – both those two words have Classical/French derivations. And would English have become the lingua franca of Europe, the means by which a Swede can talk to a Greek, or a Portuguese to a Dutchman if it did not have roots in both sides of the continent’s linguistic divide?

Then again, the force that made English the most widely spoken language in the whole world was the British Empire. But would that empire have existed, or at least been as astonishingly powerful, without William’s victory at Hastings?

The Anglo-Saxons showed little desire to colonise. The Vikings were impelled to roam the world, the British Isles included by the poverty of their own soil. But the English inhabited one of the least challenging, most agreeable environments on earth. The Normans, however, were originally Vikings: the clue is in the name ‘Norse-men’. That Scandinavian aggression and longing to roam lived on in William’s veins. It informed his style of leadership, his ravenous hunger for territory and power and the ruthless governing culture he created around him.

His influence, transported through the ages in the blood and attitudes of monarchs and noblemen may have been the spark that lit the fire of English expansionism.

The English, having mastered their home islands – harnessing the Celtic spirit in the process – then set out to rule the world. No empire in history has ever been spread across more land, in more corners of the earth, ruling more peoples than the British. William would have loved that. Others would see it as a source of shame. But would the English have become such conquerors without the Conqueror himself? Personally, I doubt it. Likewise, would England have found itself bound up with European politics to the point of joining a Union if it had remained detached from the Continent? Would it now be facing Brexit? Hmm, let’s not even go there, shall we…

David Churchill is the author of the Leopards of Normandy series – the latest of which, CONQUEROR, is out now