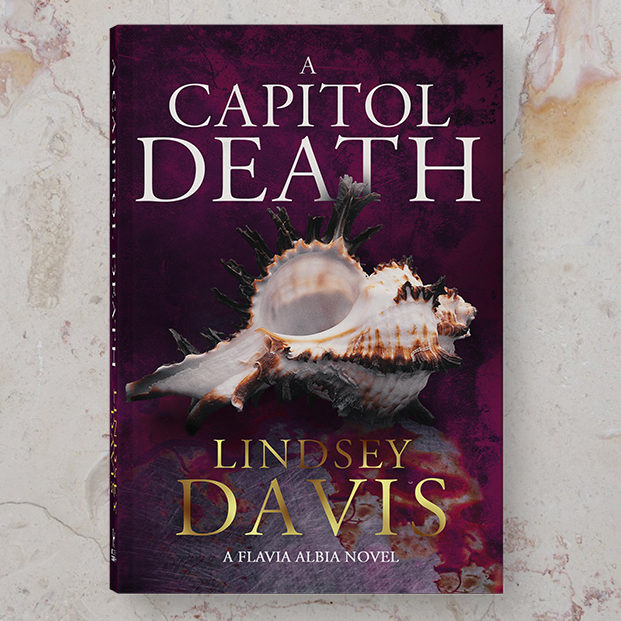

Extract: A Capitol Death by Lindsey Davis

Private Invesitgator Flavia Albia is back in Lindsey Davis’s next gripping and witty mystery set in Ancient Rome, A Capitol Death. Publishing in April 2019, we are delighted to share a sneak-peek extract of the first chapter:

A Capitol Death by Lindsey Davis

Rome: the Capitoline Hill,

November ad 89

Chapter 1

Domitian was back.

I state this in completely neutral language. Your slave must read it out to you with no hint of judgement. Even if he or she is a highly educated, clever specimen, who cost you thousands (or decades of being nice to the horrible aunt who first owned them), restraint must be shown. We don’t want a nasty execution, do we?

Domitian was back, so everybody had to look out. For me to imply that the Senate and People of Rome felt a happy respite had ended when their emperor reappeared would be risky, as risky as trying to evaluate what Our Master actually achieved during his absence abroad. That is on record – I mean, he told us. His summer-long campaign on the Empire’s borders was so politically glorious and valorously punitive that he was to be awarded a Double Triumph. He had asked the Senate for it, so the Senate would bleat their agreement because even an implicit death threat works.

A Roman triumph is a huge public event to celebrate a military commander who has successfully completed a foreign war. He rides through the main streets in a big fancy chariot. In a ceremonial procession, the general and his troops are welcomed home with wild enthusiasm; their glittering booty is admired and their exotic captives are derided or, if the poor souls look miserable enough, even pitied. It takes a very long time, costs squillions and leaves behind vast quantities of litter, which the public slaves are too tired to deal with. People behave badly. All the temples are open but there are never enough toilets. Often more divorce follows than after a Saturnalia.

To spend a full day watching a march-past is supposedly wonderful. This is Rome. Romans love street festivity. To me, they are a simple people, who never learn from their mistakes. They call it tradition. The barmier a ritual is, the more they love it.

So, our emperor was back. A triumph always has to be over someone: it must celebrate Rome conquering barbarians, our hairy, obstreperous enemies. Rome knows how to make foreigners feel sorry they exist. This double event was meant to show the world that the warlike Domitian had brilliantly walked all over the Chatti and the Dacians. They saw it differently, but they were a long way away and wouldn’t be coming to argue.

We citizens, lucky us, were to be reminded of what a dazzling emperor we had. At least until the day it happened, Domitian was camping with his troops outside Rome, as he was supposed to do. My father, ever the satirist, kept reminding us that some poor mutt in the past had had to wait five years for his triumph, but my mother, a realist, said Domitian would not be thwarted. He studied rulebooks, as paranoid tyrants do (omitting the rule that rulers should show kindness to their people). Being so meticulous, he would probably remain outside the city boundary until the triumph – though that put him rather too close to the Campus Martius, which contained the Saepta Julia where my family had its auction house. On the other hand, being Domitian, he might well decide to come in secretly, to listen to what people were saying about him in case it was treasonous so he could take revenge.

He would not camp out any longer than he had to. He was famously impatient. He would be nagging the planners to move faster. He would also want to keep close personal track of all the arrangements. Our podgy overlord liked to control every detail. He hand-picked army officers and was prone to dismissing freedmen suddenly from the palace secretariats, simply because in his view they had been around too long to be trusted. He took everything to heart. Any fault in the ceremonial would be seen as a deliberate insult to him; any omission or failure would be fatal. My husband, who was a magistrate that year, had been involved for weeks in preparations; like so many in Rome, he was now depressed and anxious. He regularly came home moaning it was all a nightmare. Pressure on the official organisers probably caused what happened one evening on the Capitol.

It began with a man falling to his death off the Tarpeian Rock. It looked like suicide. Unfortunately for those who tried to hush things up, an old woman saw him drop. With no idea of tact, she kept insisting loudly that someone had been up there with him.

She made this claim to everyone she met in the street, her neighbours, their visiting relatives, barmen, stallholders, the teacher at the infant school at the corner of her road, and some feral cats she fed. A busybody took her to the vigiles to report what she had seen. That might not have mattered since the vigiles know all about discretion, which avoids having to write reports for their prefect, but she found other outlets: because of the Triumph, Praetorian guards were crawling everywhere ‘for security’, so when the daft crone spotted one making himself unpleasant in a bar where she sometimes had a tipple, she rushed up and parked herself there to regale him with her tale.

The guards don’t bother with discretion. Any word longer than two syllables sounds intellectual to them, and intellectuals are bad people. The big idiot would have listened to her anyway, wondering if this was a plot. Praetorian cohorts are taught that it is their noble role to deal with anything that could be embarrassing to their emperor. The one whose tunic sleeve had been grabbed by the witness’s skinny fingers went back to camp, muttering. Some loon on the commissariat thought, Ho! Dealing with stuff is what we lads do, so let us bravely deal with this . . . But a crazy old lady, who actually admitted her eyesight wasn’t brilliant, was too hard to interrogate. They soon passed on the story to a civilian committee.

In a superstitious city, such an unnatural death could be seen as an omen. A bad one. In any case, if some heart- broken soul found his life too much to bear and jumped to oblivion, Domitian would be furious that a sad man with mental troubles had spoiled his day. He might even feel that having mental troubles was his own prerogative. Either way, he was unable to punish the victim, who had so selfishly put himself out of reach by dying, but he would lash out. Somebody would cop it.

The first committee shunted the problem on to another. Every group connected with the Triumph looked for a way out, which they hoped someone else would process. Time passed, as usual in bureaucracy, but this difficult agenda item would not go away.

The scene of crime, if it ever was a crime, was their big problem. The Tarpeian Rock is an execution place, starting in mythical history with a get-rich-quick wench called Tarpeia, who tried to betray Rome to a besieging army for a reward. Instead, she was crushed under a heap of shields and thrown off the Arx, the citadel. At the heart of Rome, this outcrop of rock is somewhat prominent. Not only is it an important part of the Capitol but the Capitol is where a triumph traditionally ends. Sacrifices to Jupiter and other rites occur up there, as the honoured general formally completes his task, hands back the symbols of his military power and sighs with relief that he can now go home for supper.

Nobody wanted Capitol Hill to be defiled. At the time, it was awash with workmen and temple assistants, preparing for what would be a very religious day. Jumping off the rock was the wrong kind of sacrifice.

Then things got worse. The dead man was identified.

Oh dear. He was named as a project manager involved in the Triumph. This could still have been downplayed with the right wording, except that he was in charge of transport. So not only had he been assembling a multitude of carts to amaze the crowds by carrying loot and other wonders – but his remit included the chariot. That chariot. The big beast at the climax of the procession. The specially designed chariot in which our emperor, valiant suppressor of the Chatti and Dacians, was to ride.

If someone who was meant to be buffing this fancy quadriga had killed himself before the Triumph, it was sad enough. Any suggestion that he had been murdered was a ghastly taint on the occasion. All the gods would be attending Domitian’s party: you don’t want gods to notice that your transport manager has topped himself, or been topped.

Well, all right. Maybe the gods can be paid off with a few wheaten cakes but, Hades, you don’t want Domitian to find out. He would be standing in that chariot all day, continually brooding about why the man who prepared it for him had not cared enough about his Triumph to stay around and watch.

Men on committees despaired; some succumbed to heart attacks, or said they had, before they rushed to hide in country villas. After the usual period of faffing, just long enough to lose any useful evidence, of course, someone finally applied a fix. It was solemnly decreed that they had better find out what had really happened. One of the committees dumped the problem on the aediles.

There are four of these magistrates. By definition they are among the most practical officials in Rome, though they have a big staff of experienced slaves to help them. Each man looks after a quarter of the city. The aedile who managed the Capitol swiftly claimed he already had too much to do, what with keeping top temples tidy for Domitian’s big day. He inveigled a colleague into helping out. He knew one of the others was a soft touch. This was Tiberius Manlius Faustus. My husband.

Of course, I knew what he was intending from the moment he came home and sheepishly admitted he had let himself be commandeered. I am Flavia Albia, a private informer. I specialise in domestic situations that require investigative skills. I know what husbands are like. But I had married this man on the understanding that ours would be a sharing partnership. So, Tiberius, the sly rat, passed his task to me.