Tuesday Tidbits from Karen Maitland

First Catch your crocodile

Products from the Egyptian cocodryllus or crocodile were highly prized in the medieval markets of the Middle East and Europe. Its dung was made into an unguent which was said to make aged and wrinkled prostitutes appear firm-bodied and youthful, until it ran off as they sweated from their labours. It was also said to fade freckles. And the teeth were believed to be an aphrodisiac, but only if extracted from the living beast.

The beggars are coming to town’

There were so many bogus beggars in the Middle Ages that each type of trickery acquired own name. Averers stuck on fake wax ‘boils’ or tumours made from offal to obtain alms. Biltraegerins were women who padded out their skirts to make people think they were pregnant. Granters pretended to foam at the mouth and gave themselves nosebleeds using sneezewort (yarrow) to feign the ‘falling sickness’. They begged for money or something of value they could offer at a shrine for healing, which they would then sell.

Vicars banned from Church

In 1364, Simon Langham, Bishop of Ely, censured his clergy for attending drinking parties, called Scot Ales, in their churches. He ordered his priests not to mix with actors, mimes or jesters, not to play dice and not attend the pagan drinking events that took place in the churchyards. Henceforth, priests in the diocese were only allowed to go their churches on a Sunday.

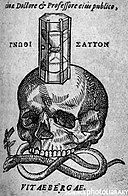

The Sweet Scent of Death

Meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmara) known as bridewort, resembles the feathers worn by brides. It was used as a flavouring for mead, so was often called meadwort. Its scent made the leaves a favourite strewing herb. However, in the Middle Ages many people would not bring the white flowers indoors, believing their perfume would cause them to drift into deadly sleep. There were often mysterious deaths in cramped cottages, probably from smoke, midden fumes or marsh gases rising from beaten earth floors. But if neighbours smelt the lingering scent of meadowsweet when they discovered the bodies, they might think the flowers was to blame.

On the 12th Day of Christmas …

in the second year of Henry VIII’s reign, the king held a banquet at Richmond, at which a ‘glistering golden mountain’ was rolled towards him, surmounted by a tree of gold and decorated with roses and pomegranates. A woman dressed in cloth of gold stepped out, accompanied by ‘children of honour’ known as henchmen who danced a morris, before retreating back into the mountain, after which the final banquet of Christmas was served. The regal version of a lady jumping out of a cake!

Fisherman’s Friend

One of the strangest saints venerated in the Middle Ages was St Rumwold or Rumbald, who died in 662 AD, aged just three days old, having precociously preached a sermon. Until the time of the Reformation, medieval fishermen returning to Folkstone sold eight whiting from each boat and gave the money to St Rumwold’s chapel. From the Reformation right up until the 1960s, fishermen still sold the fish, but used the money for a drinking party on Christmas Eve known as Rumbald Night. Legend said any fisherman who refused, would drown before the next Rumbald’s Eve.

Rock-a-bye Baby

To prevent babies being abandoned in unsafe places, some religious houses in the Middle Ages, introduced Foundling Wheels. These were swivelling barrels built into their walls that had a hole cut into one side. A mother would creep up to the outside wall, pop the baby in the barrel, ring the bell to alert the monks or nuns, then hurry away. The barrel would be turned around by those inside and the baby safely removed to be cared for in the monastery. Some Orders would only take in abandoned babies if the identity of the parents was kept secret.

Talk to the Fly

The Statistical Account of Scotland (1794) mentions the healing well of St Michael’s, Kirkmichael, then sadly overgrown. However, it notes that in the Middle Ages the well was protected by a spirit in form of an immortal fly. If a person wanted to know if their absent spouse would return, or what ailed their child, or if they should buy a particular horse, they brought their offerings to the well and by watching the fly to see if it was joyful or melancholic, how it moved and which way it turned, they deduced the answers to their questions.

Swift Justice

Medieval justice was slow as courts meet infrequently, which was a huge problem if you were a visiting merchant or pilgrim and got caught up in a civil case in the town. So, the authorities set up piepowder courts, from the French meaning ‘dusty feet’, which convened after the fairs to hear civil cases involving plaintiffs, key witnesses or defendants who were simply passing through. They speeded up justice not by changing the law and procedures, but by sitting daily and not allowing appeals to higher courts.

Rouncy (rouncey or rounsey) was an all-purpose horse, used for riding and warfare. The huge destrier, capable of carrying an armed man in full armour was the most highly prized warhorse horse of the Middle Ages, but the destrier was not a good riding horse over long distances. The agile coursers were often preferred for hard battles, but only wealthy knights could afford either of these. A poorer knight or man-at-arms used a rouncy for both fighting and distance riding. None of these horses were specific breeds, rather the size, build and training of a horse determined what it was called.

Stargazeys

Fish, usually herring or pilchards, baked individually or arranged in a row under a pastry blanket. The head and tail of the fish contained valuable oils so were not cut off but left sticking out so that the oil would run back into the body of the fish as it cooked. The pastry was hard and not usually intended to be eaten in the medieval period, so was really a method of keeping the fish basted. Clay could be used instead, especially if the fish was to be baked in the embers of a fire.

Talbot

A hunting dog bred for speed, strength and stamina, also known as a Norman Hound because it was brought to Britain with the Norman Conquest. It was about the build of the modern bloodhound and was a crossbreed. One of the breeds used was the Hubert, a black hound bred in the monastery of St Hubert in the Ardennes. Huberts had ‘red’ patches over the eyes, and if some of these dogs escaped and turned feral, they might have given rise to the legends of the black hellhounds with glowing red eyes that haunt lonely roads.

Larks claw

Delphinium consolida, also known as larkspur, larks toe and larks heel. In Medieval times this plant was used to pack wounds and treat the stings of scorpions. Oil from the seeds was extracted to kill lice. If tossed in front of any venous beast, it was widely believed the creature would not be able to move until the herb was removed.

Leek sops

A popular medieval dish. The white part of leeks was sliced and boiled until tender in a meat broth, together with lard or butter. Then the leeks and hot broth were spooned over bite-sized squares of toasted bread. On fast days, when meat was forbidden, those who could afford it substituted olive oil for the lard and white wine for the meat broth, which made a delicious and warming Lenten meal. Monks were supposed to substitute water for the meat broth during Lent, but many used wine instead.

Raphioles

This medieval dish was made from mashed pigs’ livers mixed with bread and egg yolks and formed into balls the size of apples held together with the pigs’ caul (the thin, fatty membrane that surrounds the pig’s stomach and intestines). The balls were arranged in a dish or a baked pastry case and a custard was poured in made from cream and egg yolks, flavoured with cinnamon, ginger, pepper, cloves, mace and saffron, then baked until the custard set.

Garderobe

A tiny room enclosing a medieval lavatory, often built on an upper storey projecting from an outer wall, so waste would fall through the hole beneath into a moat or river. Its height made it harder for thieves or invaders to climb up through the hole. If it was built in the middle of a complex on the ground floor, a stream would be diverted from a nearby river to run beneath it and carry off the waste. Clothes were often hung in garderobes as the stench of urine and excrement was said to keep away moths.

Hag stones

These small holed stones or pebbles were thought to guard against evil. Hung on the back of a door, they prevented the entry of evil spirits or witches. Hung over a bed, they guarded against illnesses and nightmares. If a key was attached to them, the combination of the stone and iron was thought to be a powerful amulet against bad luck and protected the house from thieves. Many holed stones can still be found on doors today, and are often hung on key rings.

Hare’s beard

This was one of the many old country names for mullein (verbascum). It was so called because the plant is covered in white hairs. In the Middle Ages it was also known as hag-taper and Our Lady’s candle, because when dried it was used as kindling, candlewicks and tapers. Witches were said to use mullein in their spells, but the plant was also thought to be effective in warding off demons and night terrors. The juice was used remove warts, and the leaves and flowers infused to make a cough, cold and bronchitis remedy.

A jolly John of Gaunt!

One Lammas Day, John of Gaunt was riding through Ratby in Leicester when some locals invited him to join in their festivities for the end of the haymaking. He enjoyed himself so much that as he left he instructed them to meet him in Leicester, saying ‘I’ll give you something to marry your lamb.’ Given his fearsome reputation only fourteen men dared go but, being in an uncharacteristically generous mood, John gave each man who did a ewe, a wether (a castrated ram) and a piece of land in Enderby, which came to be called the Ewes.

Almond milk

This was widely used in both sweet and savoury medieval recipes. It was made from any kind of ground-up nuts locally available and could be stored as a powder. The powdered nuts were mixed with meat stock, vegetable water, honeyed water or wine to make the ‘milk’, and were used in dishes where today we would use dairy milk. Animal milk went sour quickly and it wasn’t available all year round, so dairy milk was mainly reserved to make butter and cheese, which could be stored.

Duru Moon

From old English meaning door. In medieval times, many believed a waxing gibbous moon was a doorway in time into other realms. It was a place between darkness and light, a time of beginnings, and the most effective night on the month on which to call up spirits or summon the dead.

Slapcock

The medieval form of shuttlecock or badminton, known as slapcock, was played with a freshly severed cock’s head, and the object of the game was to cover the other players in as much blood, pulp and feathers as you could, while avoiding getting filthy yourself. It was played by standing in a circle and you randomly batted the cock’s head at one of the other players in the hope catching him off guard.

Plague – a Deadly Weapon

At the Battle of Carolstein in 1422, Prince Coribut, leader of the Lithuanians ordered that plague corpses, together with 2,000 cartloads of excrement, were to be hurled at the defenders of the Bohemian city. A deadly fever broke out, though it is not known if it was the plague, but the many people were reportedly saved by a wealthy apothecary who was able to treat the patients or prevent them catching the fever. 1485, near Naples, the Spanish tried a more subtle approach to biological warfare by giving their French enemies wine adulterated with the blood taken from leprosy patients.

Mortuary beast

Medieval families were supposed to give the best livestock animal they owned to the Church on the death of a loved one, to make God look mercifully on the soul of the deceased. Many were unable to afford this, for a family might lose many children. So, to persuade them to give the animal, people were told that the souls of the dead rode upon the mortuary beasts and those whose families had neglected to give a beast to God in their name would, in the afterlife, be forced to crawl on their hand and knees instead of ride.

Crooked Tables

Medieval gambling houses offered different forms of gaming including one known as tables, chequers or quek, where marbles or round stones were rolled across the board and players bet on them landing on white or black squares. The outcome could be rigged by having some of the black squares raised slightly higher than the white ones or vice versa. The chequer board pattern made it impossible to see this, especially in candle light. In 1382, William Soys cheated three men of a total of 76 shillings, 8d with such a board. He was sentenced to the pillory for an hour for three days.

Fashionable Ferrets

Medieval illustrations show noblemen and women hunting rabbits, called conies, with ferrets. But the lower classes started to acquire ferrets too, especially poachers. So, in 1390, Richard II made it illegal to own either ferrets or hunting hounds if you weren’t a landowner, declaring, ‘It is ordained that no manner of layman which hath not lands to the value of forty shillings a year shall from henceforth keep any greyhound or other dog to hunt, nor shall he use ferrets, nets, heys, harepipes nor cords, nor other engines for to take or destroy deer, hares, nor conies, nor other gentlemen’s game, under pain of twelve months’ imprisonment.’

A Horse’s Revenge

In the fourteenth century, Sir Robert de Shurland, Barron of Sheppey, killed a priest and was banished by Edward I. He swam his horse two miles out to where the king’s ship lay to beg for pardon, but on his return, a witness said his horse had made the journey by sorcery. So, Robert cut off the beast’s head. A year later, his new horse reared at that spot. Robert was thrown onto the skull of his dead horse and killed. This tale may have originated from a horse’s head and waves depicted on his tomb, probably the sign that he’d been granted the right to any claim wreck he could ride to on horseback at low tide and touch with his lance.

Karen Maitland’s THE PLAGUE CHARMER is out now

Visit her website