Battling Bandoleros in the American Civil War

Bandoleros – it’s one of those beautifully evocative words that conjures up a hundred images all by itself.

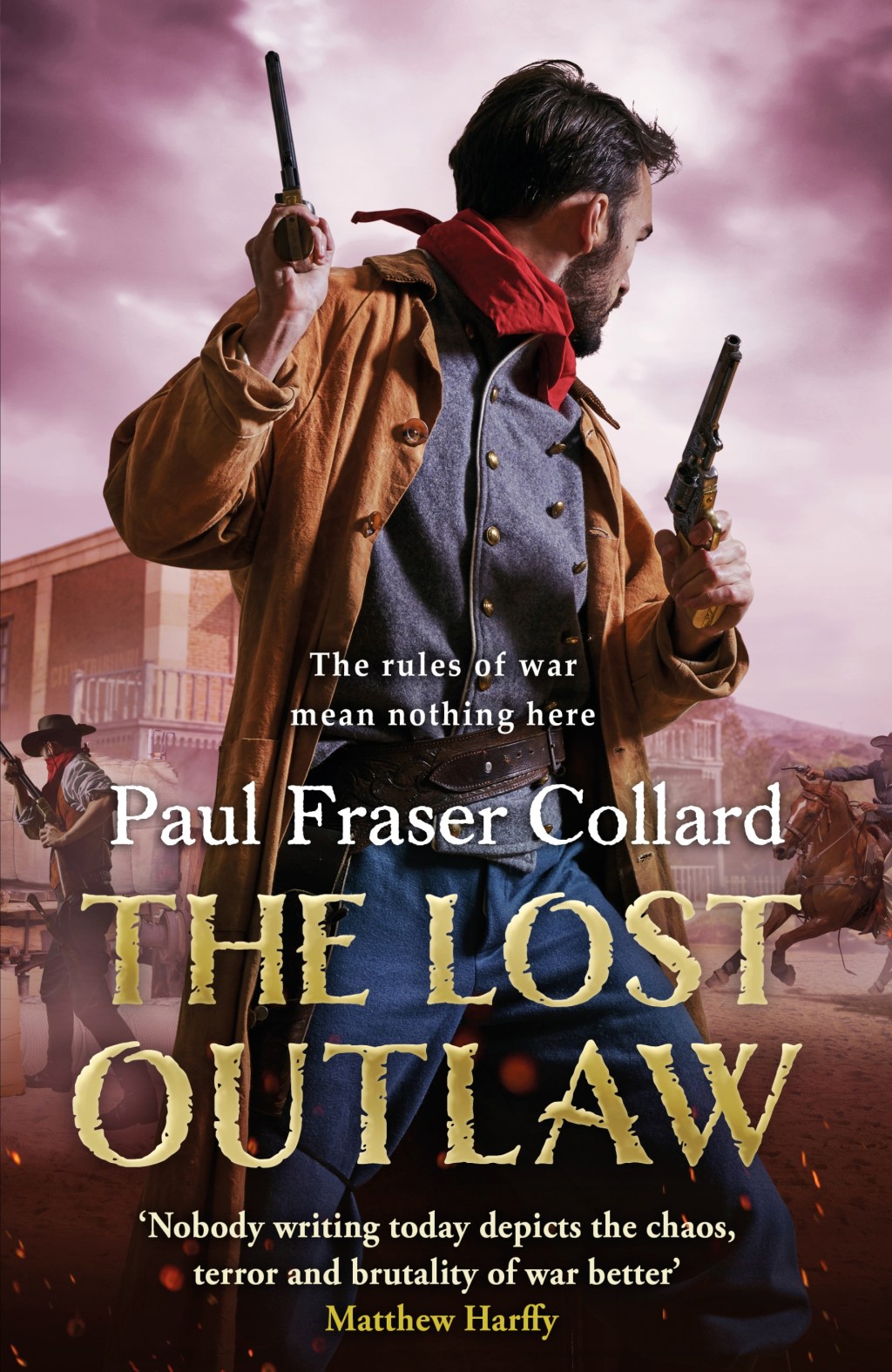

When I started planning for THE LOST OUTLAW – the eighth Jack Lark novel set in Mexico in 1863 – I knew I needed a powerful foe for Jack to face, and this time I did not have the luxury of a neatly defined enemy as I have had previously. However, it was not long before my research led me to the bandoleros who preyed on the hundreds of cotton trains making their way to Mexico from the southern states of America.

At the time of the American Civil War, cotton made up over half of the Confederacy’s exports. In an attempt to starve the Confederacy of income, the Union put in place their ‘Anaconda plan’; a thorough and effective blockade of the South’s ports that would squeeze the finances of the Confederacy and deny them the funds they would need to purchase supplies crucial to the war effort. Although not totally effective, the blockade forced cotton producers across the southern states to search for an alternative route to reach the European buyers desperate to buy the raw material on which a large part of their own economies depended. One such option was to transport the cotton by land, first through Texas and then over the Rio Grande to the neutral Mexican ports.

The task of transporting the cotton from the plantations of Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas to the ports on the eastern seaboard of Mexico was fraught with danger. Those charged with escorting the valuable cargo often had to fight off all manner of desperadoes drawn to the cotton that was worth a small fortune once it reached the Mexican ports.

The most ruthless of these renegades were the bandoleros, which of course made them the perfect foe for me to bring into Jack’s story. With this firmly in mind, I decided to create some bandoleros of my own, and so Ángel Santiago and his merciless Ángeles de la Muerte came into being. But, of course, to make them seem real I needed to base them on the real bandoleros of the period.

The bandoleros were at the peak of their powers in the spring and summer of 1863, which coincides with Jack accepting an offer of employment from the volatile wagon master, Brannigan. Two of the most notorious bandoleros of this period were José Maria Cobos and Octaviano Zapata. Frustratingly, the two get only brief mention in the few books that cover this period. Yet there are clues. In James W. Daddysman’s THE MATAMOROS TRADE we read that both Cobos and Zapata “attacked, looted, and burned, etching their names into the records.” Daddysman goes on to say that “they seemed to delight in harassing the Confederacy. Atrocity stories such as ‘murder near Brownsville…a wagoner who had delivered cotton…accompanied by a boy about fifteen years of age who was seriously wounded’ regularly appeared in the Texas Press (San Antonio Herald, May 24, 1862).” Looting and burning – words that are music to an author’s ears!

In the early 1860s, Zapata gathered a band of outlaws and raided both Mexico and Texas. By the start of the Civil War, he was already notorious and this notoriety caught the attention of the Union commanders who were only too happy to provide the bandolero with money and supplies so long as he continued to raid and pillage. This forced the Confederates to keep valuable troops tied to the border rather than freeing them to fight elsewhere. Zapata embraced his role as an enganchador to the full, so much so that he would even fly the Stars and Stripes flag during his raids, earning his men the nickname ‘The First Regiment of Union Troops.’

Zapata’s brutal campaign of late 1862, when he attacked both a Confederate supply train and a column of Mexican troops, forced the Confederates to devote more resources to his capture. That task fell to Major Santos Benavides of the 33rd Texas Cavalry. Benavides caught up with Zapata and the short skirmish that followed saw Zapata killed along with a number of his men. Such is the fate of a bandolero. For his part in the affair, Benavides was recommended for a citation. Such is the reward for a valiant officer doing his duty.

Less is known of Cobos’s time as a bandolero. We do know that in November 1863, he led a force of some two hundred men that seized control of Matamoros, the town at the very centre of the cotton trade over the Rio Grande. This revolution lasted for just one day before Cobos was executed by the military commander of the region. This stands as evidence of the ambition of these bandoleros, as well as highlighting the substantial size of the forces they controlled.

Their fates may have been grim, and their lives short and violent, but there is no doubt that the bandoleros had a lasting effect on the tales of the cotton trade. I hope that my own Ángel Santiago and his Ángeles do something to bring to life the stories of the real bandoleros, and show something of the violent struggle that existed at this time. If nothing else, they provide Jack with a cold-blooded and merciless enemy, one that he will have to fight if he is to survive.

But in Mexico, the usual rules of war don’t apply. And this time the battle might prove to be one he could lose.