Extract from K. J. Maitland’s THE DROWNED CITY

Prologue

THE BRISTOL CHANNEL

JANUARY 1606

The old man, sitting, sucking on his pipe on the quayside, was first to see it, or rather he did not see it. And that was what puzzled him. He squinted up into the cloudless winter sky, trying to judge the angle of the sun, thinking he must have miscounted the distant chimes from the church. It was a little past nine of the clock. By his reckoning, the tide in the estuary should have been on the turn, racing and foaming up the Bristol Channel, barging

against the brown waters of the River Severn and herding the flocks of wading birds towards the banks. But it was not.

The tide had started to flow in, just as it had twice a day ever since the first gulls had flown above the waters and the first men had cast their fishing nets beneath them, but now it had suddenly retreated again, as if the sea had taken a deep breath and sucked the water back out, a great blubbery beast pulling in its belly. In all his days, the aged fisherman had never known it to do that before. He half opened his mouth to say as much to the two lads

trundling barrels towards the warehouse on the corner of the quay, but he kept silent, afraid they’d jeer that his wits were wandering.

The old man struggled to his feet and shuffled along the jetty, peering down into the mud of the harbour. He knew every drop of blood, fish or human, that stained the boards of that wharf and every spar of wood that poked up from the watery silt beyond it, but he didn’t recall ever seeing the weed-covered ribs of the ancient cog ship which now lay exposed in the deepest heart of the channel.

But few other men hurrying around the quayside that morning had time to stop and gawp at old wrecked hulks, not at that hour, for it was as fine a day as any that could be expected in midwinter and no one could afford to waste such good fortune. The frost on the roofs of the cottages glittered in the sunshine and thin spirals of lavender-grey smoke rose from dozens of hearth fires as women began to bake the noonday’s bread and sweep the dust from their floors, while their menfolk, rags wound about their hands, stirred vats of boiling tar or sawed planks for new boats, some standing in deep pits so that only the tops of their heads showed above the ground, blizzards of sawdust already covering their greasy coifs.

A flock of grey plover took wing from the mud flats and wheeled over the old man’s head, their shrill cries piercing even the hammering and rasping from the boat builder’s yard. He stared back down over the edge of the jetty. Maybe his eyes had deceived him, for the tide was coming in again now, a dark snake of water writhing swiftly back up to meet the river. The estuary was filling fast. There was nothing amiss, after all. And yet . . .

The old man shaded his eyes against the dazzling sun. Something was glittering far down the estuary. He couldn’t make it out. He tottered further down the jetty. Was there a ship afire out there? Or were those not flames, but sunlight glinting off a forest of steel weapons? A Spanish invasion? It had been nigh on twenty years since those popish devils had last thought to seize the throne from Good Queen Bess, and rumour had it that King James had signed a peace treaty with them, but what Englishman would trust to a scrap of parchment? Maybe the Spaniards thought to try their luck again, knowing the new King had less stomach for a fight than the old Queen.

Three shrieking urchins rushed past the old man, almost knocking him into the water below.

It’s a huge whale, I tell you!’

‘It’s a sea dragon breathing fire!’

Alerted by their piercing yells, mothers were emerging from doorways wiping wet hands on their aprons. Men in the boatyard glanced around, then abandoned their tools and crowded towards the water’s edge, ignoring the bellows of the sawyers still deep down in the pits who were unable to understand the sudden commotion.

They all stood dumbstruck, staring at the monstrous thing racing towards them up the valley. Sparks and lights shot from it, like the giant wheels that soldiers set ablaze and sent rolling down a hillside towards an enemy camp. A haze of smoke hung in the air above it, keeping pace with it.

Somewhere in the gathering crowd, a little girl was laughing in delight, shouting that it was a magic castle and jiggling her rag doll above her head so that her poppet could see it, too. There was no doubt whatever was approaching had a strange and terrible beauty that was not of this world. Faster it came, growing ever higher, and still no one could drag their spellbound gaze from it. Then a roar burst against their ears and a great blast of wind came out of nowhere, barging through the crowd with such force that people staggered against one another. And in that instant, the enchantment that had stupefied the crowd broke and now they saw the beast for what it was. A towering mountain of black water was bearing down on them, higher than the wooden crane that unloaded the ships’ cargoes, higher than the tallest warehouse, higher even than the bells in the church steeple that had begun to toll a frantic warning.

But the warning came too late, far too late. Even as the little girl’s laughter shattered into a shriek of fear, even as the crowd turned as one to run, trampling over each other in their frantic haste, the monstrous wave struck the wharf, smashing the wooden jetty.

Metal screamed as it was ground against stone. Splintered beams and boulders, iron hooks and tin ingots were plucked up by the water and carried off like feathers in a wind. The wave charged down the streets, churning the helpless bodies of men, women and children in its cauldron, their faces battered by rocks, their bodies impaled on jagged spears of wood and twisted shards of metal.

The old man was tumbled over and over in a whirlpool of icy water, dragged down till he was dashed against something hard beneath him. He had no way of telling if he was on land or sea, they had become one raging beast. The liquid that forced its way down his throat, up his nose and into his ears was as thick as soup and so impenetrable, he thought he must have been struck blind. Instinct made him claw his way to the surface. His face burst out into the blessed light, his searing lungs fought to gasp air, but even as his eyes opened, he glimpsed a great iron-rimmed wheel hurtling towards him. He tried to throw himself from its path, but it struck before he could even turn his head, smashing his face as if his skull was nothing more than a hollow eggshell.

The giant wave swept relentlessly inland. Nothing could stop it. Walls of cottages and smokehouses appeared at first to stand defiantly resolute under the attack, only to crumble and collapse minutes later. Those still alive in the water tried in vain to grab at tree branches and chimneys, only to be ripped away from them.

The stout oak doors of churches burst wide. Wailing infants in cradles were sucked from cottages. Stone bridges tumbled like sandcastles as screaming horses and riders were swept from their humped backs. Coffins, scoured from their graves, were smashed against grinning gargoyles and fishing boats sent crashing through the roofs of houses miles from the shore.

The sea would not be bribed. It granted no mercy to the rich or to the poor. Neither the meanest hut of a blind beggar nor the grandest house of a wealthy merchant was spared. The wave surged on like a fanatical preacher determined to cleanse the world from corruption, destroy the sinners and expose all that was hidden. A man’s chamber pot hung upon a church cross; a bloodstained shift fluttered from a treetop; a forbidden holy relic

was dumped on a drowned pig and the gold coins from the miser’s chest lay scattered for all the world to steal.

Part of a wall of a warehouse, which had survived the first onslaught of the great wave, suddenly surrendered to the swirling black water, and as the stones slid beneath the sea, something tumbled out from between them and floated free. If there had been anyone to observe it, they might have thought at first it was merely a bundle of filthy rags. It twisted as the sea dragged it back and forth inside the warehouse. Only when the bundle was

flipped over by the water was it plain to see that the rags were not empty; they clung to a corpse, a woman once, though whether young or old, it was now impossible to say. Only two things remained uncorrupted: the long tawny hair that floated out around her like seaweed, and a twist of vivid blue silk cloth tied so tightly around her throat it cut deep into the rotting flesh.

An exhausted rat paddled towards the drifting body, hauled itself up and tried to shake the water from its sodden fur. It dug its claws into its once-human raft, as another surge propelled the corpse towards the back of the warehouse with such force that the head and arm of the dead woman were driven between the rungs of a ladder that still hung from the loft. The body caught there, dangling like a child’s rag doll. Even the rat abandoned it,

leaping for the ladder and scrambling up into the darkness above.

Rats always seek out the dark.

'This gripping thriller shows what a wonderful storyteller Maitland is' THE TIMES

'A dark and enthralling historical novel with a powerful narrative. The mysterious Daniel Pursglove has all the qualifications for a memorable series hero' ANDREW TAYLOR

'A colourful, compelling novel which makes a fine opening to a promised series' SUNDAY TIMES

'Devilishly good' DAILY MAIL

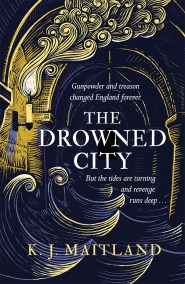

Gunpowder and treason changed England forever. But the tides are turning and revenge runs deep in this compelling historical thriller for fans of C.J. Sansom, Andrew Taylor's Ashes of London, Kate Mosse and Blood & Sugar.

1606. A year to the day that men were executed for conspiring to blow up Parliament, a towering wave devastates the Bristol Channel. Some proclaim God's vengeance. Others seek to take advantage.

In London, Daniel Pursglove lies in prison waiting to die. But Charles FitzAlan, close adviser to King James I, has a job in mind that will free a man of Daniel's skill from the horrors of Newgate. If he succeeds.

For Bristol is a hotbed of Catholic spies, and where better for the lone conspirator who evaded arrest, one Spero Pettingar, to gather allies than in the chaos of a drowned city? Daniel journeys there to investigate FitzAlan's lead, but soon finds himself at the heart of a dark Jesuit conspiracy - and in pursuit of a killer.

'Skilfully interweaves the threads of natural catastrophe, murder, conspiracy and espionage that go right to the heart of the Jacobean court' TRACY BORMAN

'Spies, thieves, murderers and King James I? Brilliant' CONN IGGULDEN

'There are few authors who can bring the past to life so compellingly - it was a genuine treat to follow Pursglove into the devastated streets of Bristol where shadows and menace lurk round almost every corner... Brilliant writing and more importantly, riveting reading' SIMON SCARROW

'The intrigues of Jacobean court politics simmer beneath the surface in this gripping and masterful crime novel... Maitland's post-flood Bristol is an apocalyptic world, convincingly anchored in its period, while eerily echoing the devastation of more recent natural disasters. I can't wait for more!' KATHERINE CLEMENTS

'Beautifully written with a dark heart, Maitland knows how to pull you deep into the early Jacobean period' RHIANNON WARD