How the history of Victorian Stockton-on-Tees influenced The Deception of Harriet Fleet

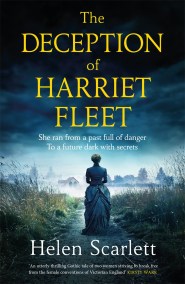

Publishing 1st April, The Deception of Harriet Fleet is an atmospheric Victorian chiller set in brooding County Durham. In this exclusive blog post for H for History, author Helen Scarlett shares with us how the history of Stockton-on-Tees influenced the setting of her debut historical novel.

Like an archaeological dig in reverse, the history of Stockton-on-Tees lies in the sky, not the ground.

Tucked away in the north east of England, Sunday afternoon in Stockton at the height of a pandemic is a pretty depressing experience. Like high streets up and down the country, it’s lined with generic nail bars, pound shops and To Let boards. But not people.

Evidence of death with a thousand cuts, inflicted by out-of-town shopping and the convenience of the internet – lockdown is just the final stab in the back. The town never really recovered from the demolition of a section of graceful Georgian coaching inns and shops in the late 1960s, which were replaced by a brutal concrete shopping centre. When I was growing up in the 1980s, people said that Stockton had the highest proportion of 18- to 24-year-olds who moved away. There were no jobs to make them stay. The sign ‘Stockton is OPEN’ takes on a certain desperate bravado in the circumstances.

Evidence of death with a thousand cuts, inflicted by out-of-town shopping and the convenience of the internet – lockdown is just the final stab in the back. The town never really recovered from the demolition of a section of graceful Georgian coaching inns and shops in the late 1960s, which were replaced by a brutal concrete shopping centre. When I was growing up in the 1980s, people said that Stockton had the highest proportion of 18- to 24-year-olds who moved away. There were no jobs to make them stay. The sign ‘Stockton is OPEN’ takes on a certain desperate bravado in the circumstances.

But look upwards and you’ll see evidence of a different story. Perched on top of twenty-first century shop fronts are upper floors, whose ornate flourishes in stone, brick, and glass tell the history of a prosperous town that positively boomed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and which led the way in the Industrial Revolution. It was once the main port for County Durham, exporting cheeses, rope, and coal around the world and gaining imports of wine in return. The town’s population grew from 10,000 in 1851 to over 50,000 in 1901, as workers poured in from all over the country, a flow only increased by the discovery of iron ore in the nearby Eston Hills.

And for the ambitious, there were huge fortunes to be made from the growing industries of engineering, chemicals, shipbuilding, and iron making.

Most famously, Stockton-on-Tees is the birthplace of the passenger train and its story is intimately linked to the development of the railways, which carried coal to the factories. In 1825, Robert Stevenson’s Rocket ran from Stockton to Darlington and a social revolution was underway. It is the rail network that lets Harriet, the protagonist of ‘The Deception of Harriet Fleet’, escape from the horrific future planned for her by Uncle Thomas Stepford and seek independence.

In fact, the novel opens at Eaglescliffe railway station, as she arrives to be a governess, the only respectable profession at the time for an educated young lady who had fallen on hard times. The former hamlet is about six miles as the crow flies from Stockton town centre and it also expanded as the railways did. The original route of the Rocket was through the grounds of the (fictious) Teesbank Hall and the first recorded fatality on a public railway lies buried in a neighbouring churchyard. The station itself was built by the Leeds Northern Railway in 1853 and was almost twenty years old at the start of the novel.

Eaglescliffe lies halfway between Stockton and Darlington and was marketed by developers as having the air of a rural retreat, while being conveniently placed for the businesses situated in the larger towns nearby. The new housing clustered around the railway, of course, and maintained an almost regimented division by social class. The small, terraced houses immediately next to the tracks were inhabited by servants and railway workers – legend has it that the cottages on Moorhouse Lane were built for the employees of Leeds and Northern who had contracted Tuberculosis. Prosperous solicitors and shopkeepers could be found in the comfortable detached and semi-detached villas on Albert Road, whose very name proclaimed its impeccable Victorian origins. Finally, the wealthiest and most successful merchants and factory owners built large mansions on the banks of the River Tees – just like the Wainwright family, who had made their fortune in the coalfields of County Durham.

I started by painting a depressing picture of Stockton on a lockdown Sunday, and I’ve also written about its glorious past, but this is a town that wants to reinvent itself for the future. There are ambitious plans to knock down the concrete 1960s shopping centre and replace it with green spaces next to the River Tees, where people can relax and socialise, as well as enjoy a spot of shopping. The Grade 2 listed art deco theatre The Globe – which hosted the Beatles and the Rolling Stones in its heyday – has been recently refurbished and will be open for business post the pandemic. Stockton has the oldest surviving Georgian Theatre in the country. And finally, independent shops like the award-winning Drake The Bookshop and Sound it Out Records have breathed new life into the lungs of this historic town.

The nineteenth century burghers of Stockton-on-Tees would approve.

'An utterly thrilling gothic tale' KIRSTY WARK

'Rich in atmosphere and suspense' BELLA ELLIS

'Two unforgettable heroines' ELLY GRIFFITHS

Dark and brimming with suspense, an atmospheric Victorian chiller set in brooding County Durham for fans of Stacey Halls and Laura Purcell

1871. An age of discovery and progress. But for the Wainwright family, residents of the gloomy Teesbank Hall in County Durham the secrets of the past continue to overshadow their lives.

Harriet would not have taken the job of governess in such a remote place unless she wanted to hide from something or someone. Her charge is Eleanor, the daughter of the house, a fiercely bright eighteen-year-old, tortured by demons and feared by relations and staff alike. But it soon becomes apparent that Harriet is not there to teach Eleanor, but rather to monitor her erratic and dangerous behaviour - to spy on her.

Worn down by Eleanor's unpredictable hostility, Harriet soon finds herself embroiled in Eleanor's obsession - the Wainwright's dark, tragic history. As family secrets are unearthed, Harriet's own begin to haunt her and she becomes convinced that ghosts from the past are determined to reveal her shameful story.

For Harriet, like Eleanor, is plagued by deception and untruths.

'Terrific characters' ELIZABETH BUCHAN

'A deliciously unsettling tale' SONIA VELTON

'Gothic ingredients given a modern twist' HOPE ADAMS