Inheriting stories of Malaysian history: Vanessa Chan’s inspiration for The Storm We Made

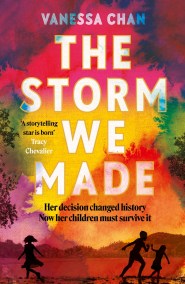

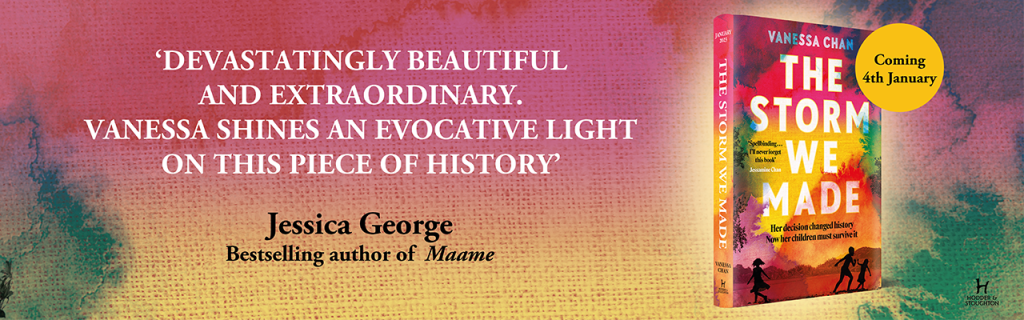

A spellbinding debut destined to become a modern-day classic, The Storm We Made by Vanessa Chan publishes on 4th January 2024. Set against the backdrop of the Japanese occupation in Malaya, it tells the unforgettable story about one woman’s decision that changes her family, and her country, forever. Below, author Vanessa Chan shares the real stories that inspired the writing of her novel.

In Malaysia, our grandparents love us by not speaking. More specifically, they do not speak about their lives from 1941–1945, the period when the Japanese imperial army invaded Malaya (what Malaysia was called before independence), tossed the British colonizers out, and turned a quiet nation into one that was at war with itself.

The thing is, our grandparents are chatty about everything else. They tell us about their childhood—the neighbors and friends they used to play with, the teachers they loved and hated, the ghosts they were afraid of. They tell us about their adulthood—the blush of first love, the terror of parenthood, the first time they touched our faces, their grandchildren. But of those four years of World War II they rarely speak, only to tell us that the times were bad, and they survived. Then they tell us to buzz off and not be nosy.

Before writing The Storm We Made, I could count on one hand what facts I knew about the Japanese Occupation. I knew that the Japanese ingeniously invaded from the north via Thailand riding bicycles, while the British cannons were pointing south at the sea. That the Japanese were brutal and killed without mercy. That they dropped red propaganda flyers about an “Asia for Asians” as they invaded, both a warning and a call to arms.

As the first grandchild on my father’s side, I spent an inordinate amount of time with my paternal grandparents, asking them many questions, to which they dotingly replied. From these childhood interrogations I gleaned just a few more facts from my grandmother: How to avoid getting hit by an airstrike (“Stay flat on the ground, and don’t get up till the plane is completely gone because they drop their bombs when they are diagonally ahead, not when overhead”). How to become your mother’s favorite (“Be a handsome boy like my brother, get kidnapped by the Japanese during the war, come back and say nothing happened”). How to make your husband jealous (“Receive a calendar in the mail every year for twenty-five years from a rare, kind Japanese man who used to work with me at the railways during the war”). As I grew older, excavating truths from my grandmother about her teens in occupied Kuala Lumpur was like playing an oral scavenger hunt. When I would ask her what life was like during the Occupation, she would always reply, “Normal! Same as anyone.”

But eventually, over the years, in an even voice that delivered only facts, I learned more—that people struggled to feed their families, schools were shut, and members of the violent Japanese secret police, the Kenpeitai, imprisoned British administrators in Singapore and quashed the Chinese rebellions in the jungles.

I put these facts away for years. I had other things to do and other places to be, I thought. I had jobs to keep, money to make, my own stories to tell. Until, in 2019, in a homecoming of sorts, I started writing the stories of Malaysia.

During a writing workshop in late 2019, I wrote what I thought was a throwaway homework assignment—about a teenage girl struggling to get home before curfew, before Japanese soldiers storm the streets. I remember the handwritten comments from the instructor: “Keep this precious thing close,” she wrote, “and keep writing it.”

So I did. I wrote through a global pandemic in my small apartment, through the premature death of my mother, through the deep loneliness of being unable to go home to Malaysia. I wrote about inherited pain, womanhood, mothers, daughters, and sisters, and how the choices we make reverberate through the generations of our families and communities in ways we often can’t predict. I wrote about carrying the legacy of colonization in your body, about being drawn to a toxic man, about complicated friendships, about living a life in fragments, about the ambiguity of right and wrong when survival is at stake. That throwaway homework assignment is now the fourth chapter of my novel.

I hope you enjoy The Storm We Made and how Cecily, Jujube, Abel, and Jasmin make their way in their world. I hope that you will feel love, wonder, sorrow, and joy as you read. And mostly, I hope you will remember their stories.

The Storm We Made

by Vanessa Chan

READERS ARE LOVING THE STORM WE MADE:

Difficult to put down once started. ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

This is not a book to be missed. ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

An absolutely exceptional book that will never leave me.⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

AS FEATURED ON BBC RADIO 4 WOMAN'S HOUR

Her decision changed history.

Now her family must survive it.

British Malaya, 1930s

Discontented housewife Cecily is seduced by Japanese general Fujiwara and the glorious future he is promising for 'independent' Malaya, free from British colonialism. As she becomes further embedded as his own personal spy, she unwittingly alters the fate of her country by welcoming in a punishing form of dictatorship under the Japanese in WWII.

Japanese-occupied Malaya, 1945

Cecily and her family are barely surviving. Her children, Jujube, Abel and Jasmin, are surrounded by threat, and look to their mother to keep them safe. But she can't tell them about the part she played in the war - and she doesn't know how to protect them.

Can Cecily face up to her past to save her children? Or is it already too late... ?

'I'll never forget this book' Jessamine Chan

'One of the most powerful debuts I've ever read. A storytelling star is born' Tracy Chevalier

'Exceptionally brave, heart-breaking, beautiful, and moving. A significant contribution to world's literature' Nguyen Phan Que Mai

'A gripping, exquisitely plotted novel. I could not put it down!' Alice Winn, author of Sunday Times bestseller In Memoriam

'A striking, moving exploration of good and evil, it is a novel that will stay with you.' Cecile Pin, author of Wandering Souls