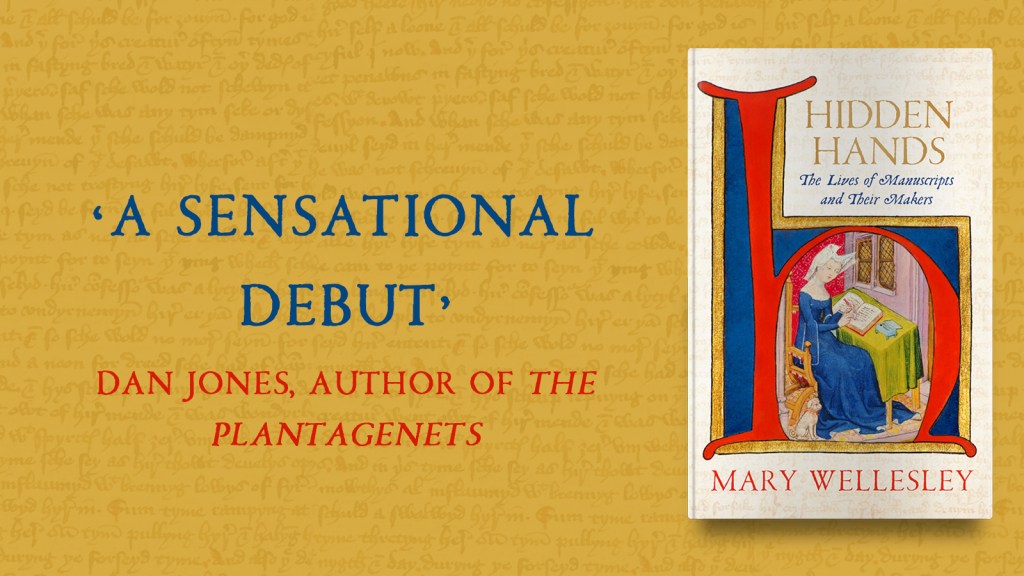

The Lives of Manuscripts and Their Makers by Mary Wellesley

Publishing 7th October, Hidden Hands: The Lives of Manuscripts and Their Makers is a stunning book about significant medieval manuscripts; their authors, their histories and the moments that mark their lifetimes. In this exclusive blog post for H for History, Mary shares why she decided to write about manuscripts.

When I sit in the velvety silence of a Special Collections reading room and turn the pages of a medieval manuscript, I feel a thrill of connection with the past. In front of me are the tangible, smellable, visual remains of many centuries ago. When I hold a medieval manuscript, what lies in front of me is not only a text, but also a collection of human stories. A manuscript will have been made by many different hands and, in its history, it will have passed through many different hands again. It will bear the traces of the people who fashioned it and loved it, perhaps of those who disdained it and those who wished to alter it, often those who found it anew in a more recent time. Many remain anonymous – shadowy figures whose work with a quill, paintbrush or tool are all that survive of them. Sometimes they come into sharper focus. My new book, Hidden Hands: the Lives of Manuscripts and Their Makers is an attempt to bring readers face to face with the people who made the English literary Middle Ages. I wanted to shine a light on the scribes, artists, authors and annotators who made these wonderful objects. Because many of these figures are anonymous, studying manuscripts gives us the opportunity to discover lost biographies. Importantly, many of these figures are the kinds of people not always lionized in our histories – anonymous artisans, people of a lower social status, minorities or women. Without manuscripts our connection to these quiet figures might be lost.

It is sometimes a struggle to explain this fact to people. Several times in the last few years I’ve been asked what my book is about. ‘Oh, it’s about sexy, sexy medieval manuscripts’, I would say, sarcastically. I started using this line when I discovered that saying ‘medieval manuscripts’ produces either a glazed or fearful expression in your listener. What I wanted to say was, ‘I’m writing about medieval manuscripts which are some of the most magical objects ever made by human hands’. I wanted to say – perhaps a little too forcefully – that medieval manuscripts deserve to be better known by the general reader. There are countless books about, for example, art history aimed at the general reader, but very few about medieval manuscripts. And yet – medieval manuscripts are no less interesting than Old Master paintings, it’s just that manuscripts are more inaccessible.

Manuscripts are inaccessible both in an intellectual sense as well as a one. They are written in obscure languages, in hard-to-decipher scripts and they are generally kept in research libraries, often available only to scholars. When they are put on public display, what we see of them is so limited. Looking at a single opening of a manuscript is like only looking at one credit-card-sized corner of an Old Master painting: it is far from being the whole picture. The medievalist Michael Camille wrote that ‘Medieval books are, of all historical artefacts, the least suited to public display in the modern museum. Behind glass their unfolding illuminations become static framed paintings, cut off from any of the sensations, texture or transport that one gets from turning their pages.’ But now, for the first time in human history, these previously inaccessible objects can be seen from anywhere in the world, in high resolution. We can now sit at home in our pyjamas and examine the Beowulf manuscript at a level of magnification that would be impossible even if we were in the reading room of the British Library, in clothing more suitable to scholarly study. Manuscripts are now accessible as never before – just waiting for us to give them the attention they deserve, because they tell us about a past which is often richer and more diverse than we give it credit for.