The Plague of Men by Karen Maitland

My new medieval thriller, The Plague Charmer, is set in 1361 and if you’d been unfortunate enough to be living in England that year, you would probably have believed the world was coming to an end because that was the year the Black Death struck again, only thirteen years after it had first ravaged England.

In the minds of medieval people, omens of impending disaster had been building steadily. The weather was unusually hot and dry causing a terrible drought so that food crops failed, as well as the hay needed for animals. On 6th May there was total eclipse of the sun at midday. On 27th May bloody rain fell on Burgundy and a ‘bloody cross’ hung in the sky over Bologna. Foxes and wolves came into towns and villages in great packs, savagely attacking humans – either because of the drought or the plague also affecting animals. The weather even had an impact on flowers and birds: a rose tree burst into full bloom for a second time that year at Michaelmas on 29th September, and birds of all kinds began to lay eggs and rear nestlings in October.

The plague broke out in London during Lent, 1361. King Edward III tried to take measures to contain the outbreak by dissolving Parliament on 15th March and banning the slaughter of animals at Smithfield, ordering that beasts could only be slaughtered at Stratford and Knightsbridge. But nothing stopped the deadly epidemic. In a cruel twist, this second wave of the Great Pestilence seemed to be attacking the young and fit – adolescents, working men and the wealthy. In some places three times as many men were dying as women, while the old and infirm were left unscathed or recovered. There have been many attempts to explain why this outbreak of the plague caused this disproportionately high death rate among fit, working-age men and young people.

The first plague of 1348 flourished in wet and cold conditions, while the outbreak in 1361 occurred during hot, dry weather and there are marked differences in some of the key symptoms between the two plagues recorded at the time. While eyewitnesses in mainland Europe recorded the presence of buboes on victims in 1347, mention of this very obvious symptom is curiously absent from many accounts of the disease when it finally reached Britain in 1348, which suggests the plague had either mutated or three different forms of the disease – bubonic, pneumonic and septicaemic plague – were spreading simultaneously. It is now thought to have been pneumonic plague which dominated in Britain in 1348, spread from person to person by coughing. The wet, cold conditions would have been perfect for transmitting this form, causing people to huddle indoors in close proximity for long periods.

But during the second outbreak in 1361, eyewitnesses in England recorded the characteristic agonising swellings in the armpits and groin which we now associate with the bubonic plague, transmitted by rodent fleas. So, was the plague of 1361 a mutation of the same one that had entered Britain in 1348, or was it a separate disease?

One possible theory that has been put forward for the differing death rates between men and woman in the second outbreak is that the form of the disease that struck in 1361 required the iron from its human host in order to multiply rapidly. Working men generally have more iron in their bodies than women of child-bearing age, the infirm or the elderly. The bacillus would therefore have been more virulent in men and also in the wealthy classes, who ate far more fresh red meat than the poor.

Whatever the cause, the second wave of plague devastated many communities because it removed the men who were needed to farm, fish and build, as well essential craftsmen like blacksmiths who produced and repaired the vital tools that everyone else needed to do their jobs including ploughshares, horseshoes, axes, knives, saws and chisels.

A tragic inscription on the church tower at Ashwell, Hertfordshire describes this outbreak of pestilence as ‘wretched, fierce and violent’ with only ‘the dregs of the populace’ surviving.

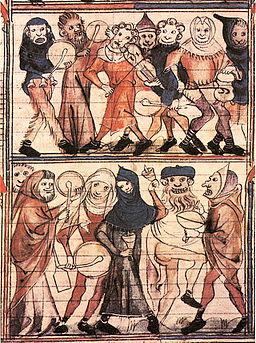

In towns, eyewitnesses reported parents abandoning their own children because they were so afraid of catching the disease. So many men died that women took ‘foreigners, imbeciles or madmen’ as their husbands. One shocked monk complained that the widows even took their ‘own kin’ to bed, giving birth ‘without shame to bastards’ and treating fornication and incest as a game. But since many priests and monks were inclined to condemn all women as harlots, however chaste they were, it was probably only a few women who behaved in this way. But, unsurprisingly, there are many of accounts of women crazed with grief or else numb from the horror of it all.

By September the plague had reached the Midlands and swept across northern England and Wales in October. Thankfully by Christmas of that year it had died away in England, though it was still raging in Scotland and Ireland.

But just when people in England were beginning to rebuild their shattered lives, a final tragedy occurred. On 15th January, the British Isles were hit by the St Maurus’ Day wind, the most violent hurricane-force wind ever to strike Britain in recorded history. It brought cathedral spires tumbling, including the cathedral tower at Norwich, and destroyed homes, harbours and hundreds of windmills used to produce flour. The disaster was made worse by the fact that so many of the craftsmen and workmen needed to rebuild these smashed buildings had been killed or rendered disabled by the plague.

But the wind brought good fortune to some. The foresters had plenty of fallen trees to sell for the rebuilding of homes, churches and ships and King Edward III consoled himself over the loss of his two daughters to the plague by fiercely maintaining his rights to ‘treasure trove’ from the numerous ships that were wrecked along the English coast during the storm. As my character Lady Pavia in The Plague Charmer might have remarked, ‘It is an ill wind that blows no man profit.’

Karen Maitland’s THE PLAGUE CHARMER is out now