What’s a passionate man to do? Sarah Shoemaker

Love, marriage and divorce in the world of Jane Eyre

Sometimes, seeing Mr Rochester tied down to an insane wife and loving Jane, it would seem easy to ask: Why doesn’t he just get a divorce? That may be cruel, but, indeed, what kind of marriage have they anyway? Or have they ever had after the first few months? I’m sure I must have asked that question when I first read Jane Eyre.

Some history will make Rochester’s situation a little clearer: Before the latter part of the nineteenth century, marriage, in most places in the world, was an economic, societal and/or political matter. People of the upper classes got married to preserve family fortunes, to link together families of common status or with common interests, or to link nations or principalities. If none of those reasons pertained, people didn’t necessarily get married, for if there was no family fortune, then there was no reason to assure inheritance; if there was no social standing, there was no reason to cement status; if there was no familial power, there was no power to maintain. And, indeed, many people in the lower classes did not marry.

In Mr Rochester and Jane Eyre’s England, divorce would only be granted by Parliament for reasons of inheritance, and only when the wife was caught (with witnesses) in a compromising situation with a man other than her husband. The rationale for this was that the husband thus could not be sure her children were his own, and with that uncertainty of parenthood, legal inheritance would be questionable. (A wife could not be granted a divorce simply because wives could not own property.)

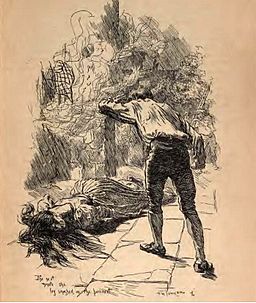

Rochester thus finds himself in a difficult position: he has been tricked into marriage with a woman who will never be a wife to him, and he cannot divorce her. And then he meets Jane Eyre, whom he learns to love, yet he knows that the law will never allow a marriage between them as long as Bertha lives. What would a reasonable man do in this situation? What would a passionate man do? Of the choices left to Rochester, what would we have him do? I struggled with that, as I know he did, and Bronte must have.

One of the most difficult parts of Mr Rochester for me to write was the growing relationship between Rochester and Jane. Rochester is, of course, one of the landed gentry, just a step down from nobility, while Jane is a governess, a step up from a servant. It was a very delicate thing to bring two people of such disparate stations in life together in a romance in the early nineteenth century. She cannot be seen as overstepping her bounds, and he cannot be seen as taking advantage of an underling.

In today’s world, where a prince of the realm can romance and marry a commoner, such a situation does not seem so fraught with problems as it was in Jane Eyre’s time. Then, if the lord of the manor made advances toward a governess, her position – her livelihood and her reputation – was at stake if she refused. And if a governess did happen to be attracted to her employer, she dared not show it for fear of immediate dismissal. Both Jane and Rochester were in impossible situations.

For that reason, Rochester felt himself compelled to force a reaction from Jane, either as a result of jealousy on Jane’s part or as a response to Jane’s understanding of what damage to little Adele would be done if Blanche Ingram became Rochester’s wife, to say nothing of how totally incompatible Rochester and Miss Ingram actually were. Pushing Jane to make the first move was the only way for him to be sure that she would accept him as a suitor and not a lecherous employer. Rochester’s apparent insensibility – talk of marriage to and the attractions of Miss Ingram, his suggestion that Jane can go into the employ of the ridiculously-named Mrs Dionysius O’Gall of Bitternutt Lodge can then be understood as intended provocations hoping for a reaction from Jane. But Jane staunchly refuses to reveal her feelings, until, at last, Rochester pushes Jane beyond bearing, and, in the end, his scheme works.

Interestingly, toward the end of Jane Eyre, Bronte has Jane returning to Rochester without knowing that he is now free to marry. Jane returns not because he is free to marry, but because she has an inheritance, she is now independent and she can face Edward – and ally herself with him – as an independent woman.

I did not realize, when I started this novel, how difficult it would sometimes be to try to peer into Edward Rochester’s mind. Yet, I trusted Charlotte Bronte to have written a decipherable character, and I thoroughly enjoyed the challenge of attempting to understand him and to paint more fully such a complex person.

Sarah Shoemaker is the author of MR ROCHESTER