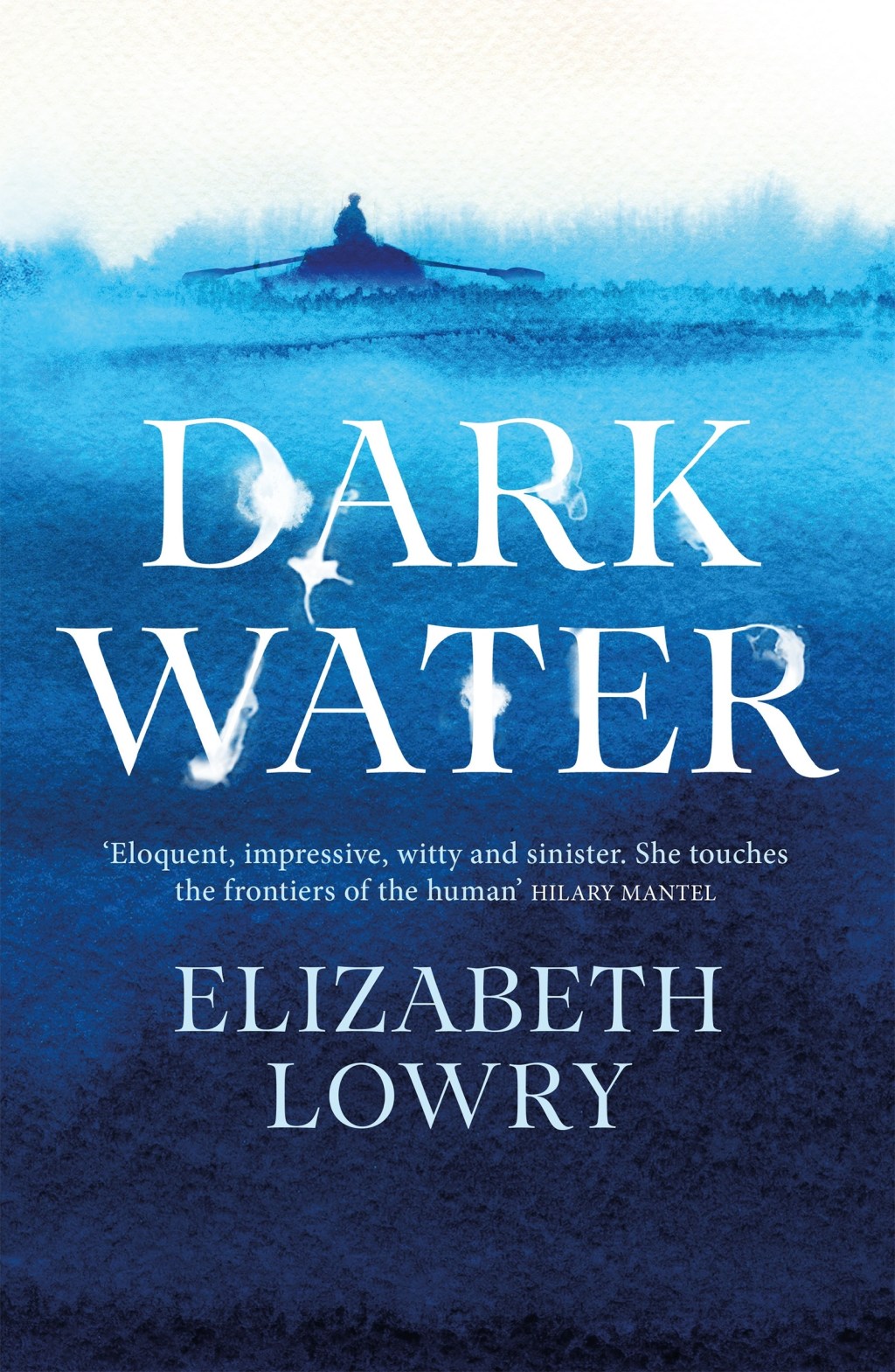

How the Massachusetts Coast Inspired the Setting for Elizabeth Lowry’s Dark Water

Dark Water grew out of a love of the Massachusetts coast, and of Poe and Melville, and of their maverick nineteenth-century American sensibility. Those quest tales of land and sea, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym and Moby-Dick, are archetypal stories of escape from home and family, of a rite of passage; each, in its own way, charting the contradictions and tensions of American society at a time of great change. I wanted to write a story which shared not just the landscape (and seascapes) of these narratives, but something of their freshness and violence and sense of mystery – the mystery of a pre-Freudian age – while calling attention, as they do, to the problem of representing human truths.

A quest implies a question, a probing of what is. At the heart of Dark Water are the twin questions of power and personality, and how these are expressed through human systems. Boston and Nantucket, the one a sophisticated harbour city, the other a tiny island, self-sufficient, enclosed, are in the story both bounded societies and at the same time places of transformation, intimately connected with the sea, the book’s motif for the unconscious. Dark Water is set in the early days of mind-doctoring, and explores the awful paradox that, while nothing is nearer to us than ourselves, very often nothing is more unknown to us than our own being. Two decades before Dorothea Dix set out to reform the care provided in mental hospitals across America, a system of compassionate management was already being practised at the Charlestown Asylum for the Insane outside Boston (the early incarnation of McLean, the psychiatric hospital today located in Belmont). This – or a fictional version of it – is where Hiram Carver, the book’s narrator, works.

In Carver I hoped to create a protagonist who could test all sorts of boundaries; whose role, like that of Poe and Melville’s characters, is to challenge the collective, to journey outside the permitted zone, to ask the difficult questions. A young man sets out to heal a wounded hero, to resolve his own inner tensions, and to explore the mystery of human nature, particularly our primordial twin instincts for violence and hero-worship. Carver fails in his personal quest: despite having set himself all along against the confining social structures of his world, in the end he becomes the thing he hates. He writes his story in 1855. Lying just over the horizon of the book is the war of 1861 to 1865, when what is submerged or ‘obscure’, to use Lacan’s word, rises to the surface and is realized as violence on a national scale – opening up these ancient questions about sacrifice and heroism anew.

I had a more personal reason, too, for setting Dark Water in America: its eastern seaboard is where I was born, and although I left at a very young age, it retains, for me, a flavour of home. American English was the first form of English I ever spoke, and it felt natural to revisit both the country and the language in fiction. As Carver says in the book, when approaching the asylum for the first time, ‘When is our real home ever locked?’