The Big Freeze

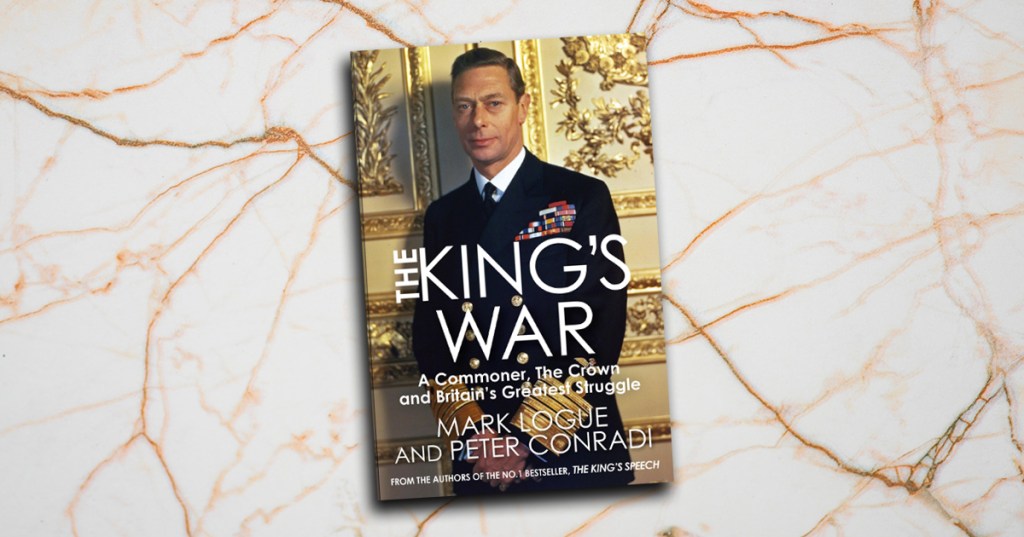

Extracted from The King’s War, by Mark Logue and Peter Conradi, an incredible insight into the monarchy during the darkest days of WWII. The King’s War draws on diaries, letters and other documents left by George VI’s speech therapist, Lionel Logue, and his wife, Myrtle. It provides a fascinating portrait of two men and their respective families – the Windsors and the Logues – as they together faced up to the greatest challenge in Britain’s history.

The first full year of the war began with a big chill: the newspapers proclaimed it the coldest since the Battle of Waterloo. The Thames was frozen for eight miles between Teddington and Sunbury, and ice covered stretches of the Mersey, Humber, Severn, the Lakes and all the Scottish lochs. Hundreds of barges were unable to move on the Grand Union Canal. Temperatures in central London were below zero for a week and there was skating on the Serpentine on six inches of ice. Trains were trapped in snow drifts, water pipes froze, boilers exploded and birds were said to have fallen from the sky into the Channel. The average temperature in January was minus 1.4° C.

Despite the war and the worsening weather, the Logues had enjoyed a remarkably normal Christmas break – even though, as had become a habit, Lionel spent the day itself with the King. Guests began arriving at Beechgrove on the twenty-third, which was a Saturday. Together with the Logues, there would be ten of them for Christmas. The visitors would be staying in the house because the fog made travelling almost impossible, even within London. Myrtle viewed the challenge ahead with some trepidation: it would be the first time since they had left Australia that she had to look after so many people without any staff to help. In the run-up to Christmas she had also been struck down by a bout of bronchitis – although at least this afforded her time to finish knitting a pullover for Valentine.

On Christmas Day itself, they had a ‘jolly cold luncheon’. ‘Champagne cocktails at 6.30 p.m.; the presents given, goodness knows when we shall be able to afford champagne again,’ noted Myrtle. As the guests washed up after dinner, they listened to Gracie Fields on the radio singing to the troops. ‘Didn’t have our usual dance as nobody felt inclined for it.’

By 27 December the guests had all departed, and life settled down into the usual lull between Christmas and New Year, though it was enlivened by the arrival home of Valentine, who had been given a ten-day break from the hospital after having worked all through Christmas. It began to snow; Beechgrove, to Myrtle’s eyes, ‘looked divine’, even though Valentine and Antony, who was back from Leeds for the holidays, were disappointed that not enough of it had settled to make it worth getting out their toboggan. On New Year’s Eve, they all set off for a party hosted in Wimbledon by their Australian friends, Gilbert and Mabel Goodman, which meant a ten-mile drive through blacked-out London. ‘The fog came up and we had the most terrifying experience getting there in Valentine’s little open sports car,’ Myrtle wrote in her diary. ‘Dozens of people telephoned cancelling, we had another party in town to go to, left early and went to the Lyceum club and saw the New Year in, then started for home, which took 1½ hours instead of 30 minutes. Pedestrians led us with torches, their hands on the top of the car. I really must not try an experience like this again.’

And then it was all over. That Sunday, Antony left early to go back to Leeds to look for new digs; Valentine stayed until after lunch. ‘It is lonely without them,’ wrote Myrtle after they had both gone. ‘Back again to the old routine. Frost again, and snow nearby, the whole of Europe suffering likewise.’

In the days that followed, Myrtle chronicled the worsening arctic conditions engulfing London:

9 January: ‘Freezing today, so I’m not allowed out, so have decided to repair bed linen, have not had to do this myself many years.’

10 January: ‘Fall of snow, which had hardened on top of frost and making roads very dangerous, so decide to clear out the drawers of discarded toys belonging to the boys . . . This cold is certainly keeping the Huns quiet.’

18 January: ‘This icebound land is becoming boring, our place is a sheet of snow, with only the marks of the birds across the smooth surface.’

Keeping a large house such as Beechgrove liveable in such temperatures was a near impossible task. At the beginning of the winter, to save money, Lionel and Myrtle had decided to heat only the few rooms they were using and to turn off all the radiators in the top part of the house. On 19 January, as the temperature plunged, three of the radiators burst. Myrtle spent two hours fighting an ever increasing cascade of water using a spanner as a lever until she managed to shut off the stop cock. ‘Oh boy, do we have fun,’ she wrote. The next day, according to Met Office records, after an early low of close to minus 9° C, the temperature crept up only as high as minus 2.4° C.