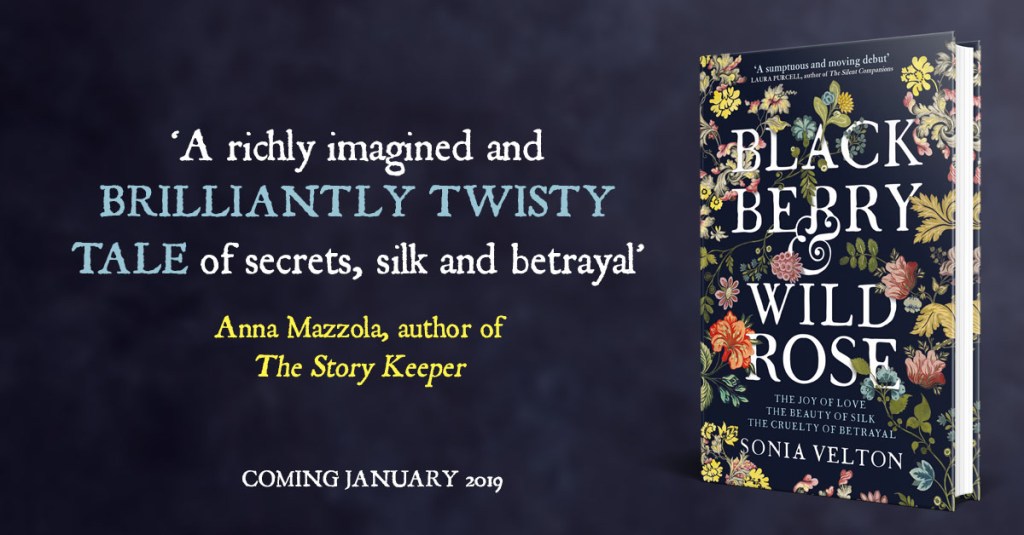

The World of Blackberry and Wild Rose by Sonia Velton

History buffs, get excited. Sonia Velton, author of Blackberry and Wild Rose, is about to take you on a tour of Eighteenth Century Spitalfields and the Huguenot silk weavers who lived there…

Take a walk through the streets of Spitalfields and you can still see and feel the presence of the Huguenot silk weavers. They are there in the wooden spools hanging from the weavers’ houses, they are there in the shadows of the eighteenth century sundial on what was once La Neuve Église, and they echo through the street names; Fleur de Lis and Fournier Street.

I remember the first time I paused outside a terrace of Georgian townhouses and looked up to see the ‘long lights’, huge windows built into the attics. When I began to research the area and discovered that they were silk weaver’s lofts, it was the beginning of my fascination with the Huguenot silk weavers of eighteenth century Spitalfields. I kept imagining these tall and gracious buildings alive with the clack-clack-boom of the drawlooms. The whole of Spitalfields would have thrummed with their sound, and everywhere, from the market to the modest weavers’ cottages, would have played a part in an industry which came to produce some of the most exquisite silks ever made. It was this world of immigrant French silk weavers, their lives and loves, and of course their spellbinding silks, that formed the setting for my novel, Blackberry and Wild Rose.

On one of my many Sunday trips to Spitalfields market (I lived a stone’s throw away in Bethnal Green) I noticed a blue plaque on the corner of Princelet Street; ‘Anna Maria Garthwaite 1690-1763 Designer of Spitalfields Silks lived and worked here’. A woman! I was hooked. From Princelet Street, then, to the Victoria & Albert Museum. It can be hard to pinpoint the moment an interest becomes an obsession, but that day, viewing Garthwaite’s original water colour designs and the incredible silks themselves, still as delicately luminous as they were almost three hundred years before, was probably that moment for me.

I was as interested in Anna Maria herself as I was in the hundreds of beautifully painted silk patterns that made her one of the foremost silk designers of the eighteenth century. How did this daughter of a clergyman from Leicestershire use her talent as an artist, and passion for painting flowers, to become a pre-eminent silk designer? How did she learn the necessary technical skills to prepare the mise-en-carte for the drawloom with mathematical precision? After all, many silk designers were already weavers or master weavers themselves.

Unfortunately this kind of detail about her life has not been recorded, but we do know that she was a life-long spinster, never marrying and living with her sister and their female ward. She was already in her early forties when she first moved to Spitalfields and began to send out her work to master weavers signed only A. M. Garthwaite. An unlikely heroine for a book, perhaps?

Of course, the personal life of Anna Maria Garthwaite bears no resemblance to Esther Thorel’s, the protagonist of Blackberry and Wild Rose. However, when I created Esther’s character, I did so in the certain knowledge that there was historical precedent for a woman succeeding in the male-dominated world of the Spitalfields’ silk industry by sheer force of talent and determination, with no formal training and without a male patron.

As I began to research my novel, it became clear that the beauty of the Spitalfields’ silks belied the grim reality of life as a journeyman silk weaver. The industry was beset by industrial conflict. At the time, I was a solicitor specialising in discrimination law and acting mainly for individuals and trade union clients. When I discovered that the militant journeyman were among the first pioneers of the trade union movement, forming illegal ‘combinations’ which met in secret, it resonated with the employment lawyer in me. The stock response of the eighteenth century mob was to riot, and the Cutter’s Riots of the 1760s provided the perfect troubled setting in which to drop the fictional Thorel household.

Blackberry and Wild Rose is a book of contrasts: the ethereal beauty of figured silk, and the finger-numbing hours of repetitive pulling on ‘lashes’ and ‘simples’ endured by the drawboys; the apparent piety of a religious household and the flawed reality of marriage; the strict moral code of the Huguenot community and the chillingly expeditious way eighteenth century justice was dispensed; the tasteful privilege of Esther Thorel’s existence, and the life of her new lady’s maid, Sara Kemp, full of chamber pots, brick dust and relentless drudgery.

Our perceptions of the eighteenth century are shaped by the moral art of William Hogarth. If Industry and Idleness speaks of the journeymen weavers, it is the first plate of A Harlot’s Progress which introduces Sara Kemp as Esther Thorel’s dual narrator. The classic cautionary tale of the naive young country girl arriving in London under the watchful gaze of a notorious madam. Sara allows us to peer beyond the elegant parlours and ochre-coloured walls of the Thorel household and glimpse the East End’s dark underbelly.

This novel, in its various drafts, had many titles but none was quite right. Looking for inspiration, I turned to my original notes, made the day I had visited the V&A. I had been captivated by one particular silk pattern. It’s most likely that it was one of Garthwaite’s own as almost all the patterns I looked at were, but it could also have belonged to another designer as I did not write down its artist, just its enchanting name, scrawled messily right across my page: Blackberry and Wild Rose.