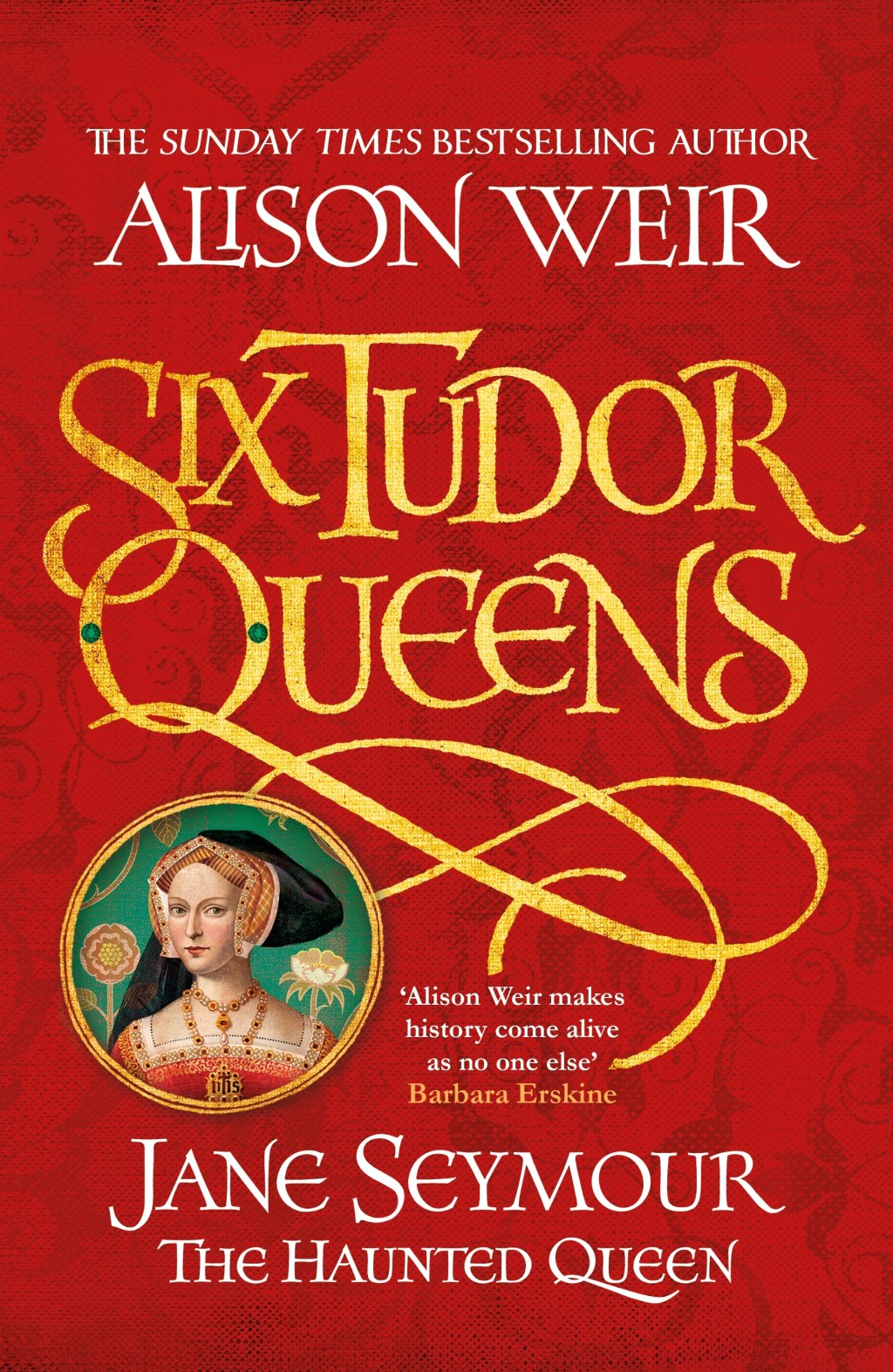

Scandal in the Seymours by Alison Weir

It appears likely that there was some kind of scandal in Jane Seymour’s family before she came to court. By 1519, her brother Edward had married an heiress called Catherine Fillol. She bore two sons, John in 1527 and Edward in 1529, then seems to have retired to a convent. Mysteriously, her father, Sir William Fillol, in his will of 1527, directed that ‘for many diverse causes and considerations’, neither Catherine ‘nor her heirs of her body, nor Sir Edward Seymour her husband in any wise’ were to inherit ‘any part or parcel’ of his lands; and he left her forty pounds – about £17,600 now – ‘as long as she shall live virtuously and abide in some house of religion of women’. He died in July 1527, but, as Catherine gave birth to her second son in 1529, she evidently did not immediately observe her father’s condition.

Possibly a scandal then came to light, and she was repudiated by Edward Seymour. Left destitute, she probably had to seek refuge in a nunnery so that she could claim her inheritance. She had died by early 1535, whereupon Edward Seymour immediately married the formidable Anne Stanhope, a lady whose pride would become notorious.

There is some later evidence that Catherine had had an affair with her father-in-law, Sir John Seymour. A marginal note in a seventeenth-century baronage in the College of Arms states that Edward repudiated Catherine ‘because she was known by his father after the nuptials’. The only other evidence comes from the historian and theologian Peter Heylin, who, in 1674, claimed that a magician had conjured a ‘magical perspective’ for Edward, enabling him ‘to behold a gentleman of his acquaintance in a more familiar posture with his wife than was agreeable to the honour of either party. To which diabolical illusion he is said to have given so much credit, that he did not only estrange himself from her society at his coming home, but furnished his next wife with an excellent opportunity for pressing him to the disinheriting of his former children.’ It seems that Edward did have suspicions about the paternity of his sons by Catherine, for he disinherited them both, at Anne Stanhope’s instigation, in 1540.

If an incestuous liaison was involved, there was all the more reason for secrecy and the affair being hushed up, but we should remember that Sir William Fillol disinherited Edward as well as Catherine, for reasons that are not clear.

For more on Alison’s Six Tudor Queens series visit the website