Alison Weir introduces Anna of Kleve

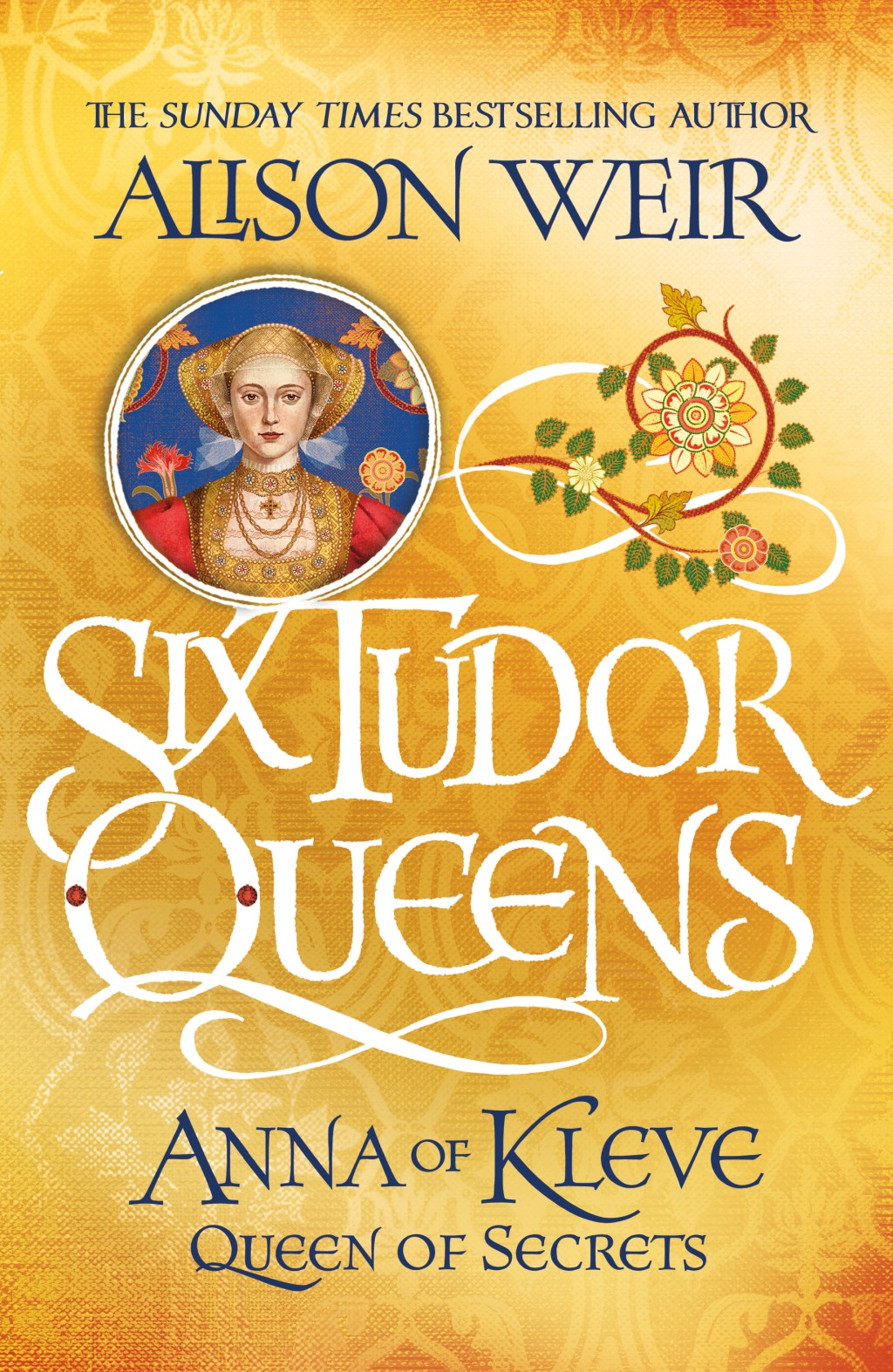

Most people think of Anna of Cleves – or Anna of Kleve, as she should be known – as the luckiest of Henry VIII’s wives. Having re-researched her story in depth for Anna of Kleve: Queens of Secrets, the fourth novel in my Six Tudor Queens series, I am not so sure that is true.

Anna should have had it all: a crown, a great marriage to a powerful king, wealth, influence and popularity. But it was all snatched from her, for reasons that are still not fully clear.

When, within a month of Jane Seymour’s death, Henry VIII was ‘framing his mind’ to marry a fourth time, for the good of his realm, there was a long search for a suitable bride. At length Henry decided upon a German princess, Anna of Kleve, of whose beauty he was assured. He sent his court painter, Hans Holbein, to paint her portrait. An ambassador vouched that it was a good likeness, but Anna did had no talent for any of the courtly accomplishments that Henry admired in women. Yet he was enchanted by her portrait and pressed ahead eagerly with the marriage negotiations. Her arrival in England was delayed by storms, fuelling the King’s impatience. Learning of her coming, the ardent suitor rode through the winter night to Rochester to meet his bride, to nourish love, as he told everyone.

All the world has heard how Henry, seeing Anna for the first time, felt a deep aversion to her. Few, however, have paused to wonder what Anna thought of Henry… It was the most disastrous of beginnings.

Preparations for the marriage went ahead. The King showed Anna every courtesy, while doing his best to wriggle out of the marriage contract, but it was seemingly watertight, and he ‘needs must put his neck in the yoke’, as he gloweringly put it. The marriage took place in January 1540, but was not consummated. On the wedding night Henry pawed Anna’s breasts and belly, but ventured no further, for, by their looseness and other tokens, he was to declare many times, she was no virgin. Has anyone ever wondered what he might have meant?

Was Anna an innocent, outraged by the King’s treatment of her person? She told her ladies how the King came to bed, kissed her and bade her, ‘Good night, sweetheart’, and how in the morning he kissed her and said, ‘Farewell, darling.’ There had to be more than this, they told her, if there was to be a prince in due season. But Anna was perhaps less innocent than she liked to make out. My research revealed a thread of evidence which might suggest that this was a lady with secrets – one who had a past.

In the spring, Anna was sent to Richmond Palace while Henry searched for a pretext to have their marriage annulled. It was dissolved after only six months, and his very generous divorce settlement came as a surprise and relief to her. She was now a woman of means with a generous income, great houses, and the honour of being able to call herself the King`s dearest sister. She was happy to stay in England. Against all the odds, she became firm friends with the King, and even with Katherine Howard, the Queen who immediately supplanted her. Soon, Anna was in such high favour that there were rumours that the King would take her back.

Surprisingly, it was Henry VIII, the husband who had repudiated Anna, who became her best friend in the years after their marriage was annulled. While he lived, her interests were protected, and she was treated with great esteem. When he died, things began to go badly wrong for her. Money, or the lack of it, was a problem that never went away. The houses she loved were taken from her. There were disturbing intrigues in her household, which caused her great grief. She came under the influence of a dangerous man, and her association with him laid her open to the suspicion of treason, and may well have cost her the favour of her former friend, Queen Mary I. Lucky? I don’t think so.

ANNA OF KLEVE: QUEENS OF SECRETS, the fourth in Alison Weir’s Six Tudor Queens series, is out now.