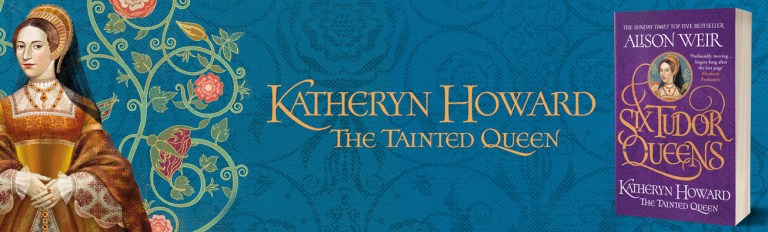

KATHERYN HOWARD: ‘SOMETIME A QUEEN’ by Alison Weir

The story of Katheryn Howard, Henry VIII’s fifth wife, is one of the saddest and most shocking episodes in English history. It is also the subject of a very modern debate. Was Katheryn a promiscuous wanton, a capricious flirt, a needy young girl looking for love, or a much-misunderstood political animal?

Many are convinced that she was an abused child, the tool of ruthless men who would nowadays be prosecuted as paedophiles. Yet the best evidence shows that she was in fact older – a joyous young woman who drove her own destiny, but became caught up in a situation from which there was no disentanglement. Poorly educated and naïve, she was ill-equipped to be a queen. Her own cousin, Anne Boleyn, was beheaded for adultery and high treason. Katheryn should have learned a lesson from this. Sadly, she didn’t. What happened in the dreadful three months after her misconduct came to light was one of the most difficult stories I have ever had to write.

In her short life, Katheryn loved four men; all contributed to her ruin, and it seems that the only man who truly loved her was the one who sent her to her death. She was the victim of her powerful and ambitious relations: her neglectful step-grandmother, the ruthless Duke of Norfolk, the sinister Lady Rochford and the volatile Francis Dereham.

Telling Katheryn’s story from her own perspective offers new insights. Did she and her kinsman Thomas Culpeper actually commit adultery? Was there love on both sides? Or were Culpeper and Lady Rochford in league with a political agenda? If not, then one can only draw the most unsavoury conclusions about Lady Rochford.

When she became queen, Katheryn had everything going for her – so long as her past did not catch up with her. Henry VIII was an adoring, attentive husband. Katheryn’s fall was his tragedy as much as hers. Did he really want her to be put to death? He had loved her so much, and his grief at her betrayal went deep. He was lenient in his treatment of her: he did not send her to the Tower while her offences were investigated, but to the relative comfort of the dissolved abbey of Syon. He did not immediately deprive her of the status of queen – not until her affair with Culpeper came to light. It was said that he would ‘bear the blow more patiently and compassionately and would show more patience and mercy than many might think – a good deal more tenderly even than her own relations wished’. He was unusually merciful in commuting Culpeper’s sentence – this was a privilege customarily extended only to peers of the realm. He kept six of the jewels Katheryn had worn; they had perhaps been her favourites.

But the reformist radicals who dominated the Council and had brought down the Catholic Howards at a stroke were not about to collude in their restoration. Under the pretext of sparing the King pain, they took charge of the investigation with zealous, unremitting thoroughness and a studied determination to find evidence of adultery. With Henry in seclusion, refusing to deal with business, they had a free hand. In a speech to Parliament, the Lord Chancellor ‘aggravated the Queen’s misdeeds to the utmost’, as did everyone else involved in the investigation of her offences. The councillors’ insistence on not publicly mentioning anything ‘which might serve for her defence’ shows how determined they were to bring down the Queen.

After Katheryn was condemned, the King, ‘wishing to proceed more humanely, sent to her certain councillors to propose to her to come to the Parliament chamber to defend herself. It would be most acceptable to her most loving consort if the Queen could clear herself in this way.’ An Italian envoy heard that Henry meant to condemn her ‘to perpetual prison’. The Imperial ambassador, Eustache Chapuys, wondered: ‘Perhaps, if the King does not mean to marry again, he may show mercy to her or, if he finds that he can divorce her on the plea of adultery, he may take another thus.’ The unreliable Spanish Chronicle (perhaps not so unreliable in this case) stated: ‘The King would have liked to save the Queen and behead Culpepper, but all his Council said, “Your Majesty should know that she deserves to die, as she betrayed you in thought and, if she had had an opportunity, would have betrayed you in deed.” So the King ordered that they should both die.’

Petitioning Henry not to ‘vex himself with the Queen’s offence’ and to give the royal assent to the Bill of Attainder by letters patent under his great seal reflects a determination on the part of the councillors that their master should have little opportunity to relent, and that the Queen must die. The lords had their way. Katheryn was condemned, and the King lifted no finger to save her.