Inside the Gobelins Manufactory by Ann Marti Friedman

The Gobelins Manufactory or the Manufacture Royale des Meubles de la Couronne, to give its official title, is the setting for my new novel, A Fine Tapestry of Murder. Founded by Louis XIV in 1662, its tapestry studios are still active today. Louis’s generous patronage attracted the best craftsmen of Europe to the Gobelins. It served as workshop and home to Flemish tapestry weavers, the French dyers who supplied the yarn, English silversmiths, Italian sculptors and craftsmen in marble, and French makers of marquetry furniture of all kinds. Collectively, under the direction of the painter Charles Le Brun (1619-1690), these talented men produced the tapestries, monumental silver vessels and elaborately decorated tables and cabinets for the King to use in his palaces or to give away to show off the wealth of France.

The piece, Louis XIV’s visit to the Gobelins 15 October 1667, part of the Histoire du Roi series commemorating significant events of his reign, shows us examples of the tapestries, marquetry furniture and silver made in the Gobelins. Louis is the figure in the red hat at left; Le Brun is the second figure to the right of the King. In the novel, Anne-Marie, my heroine, visits the silver workshop and sees a table being made there. Alas, none of the massive silver objects made for Versailles and other royal palaces have survived, as they were melted down in 1689, during one of Louis’s endless wars, to be turned into coin to pay the King’s troops.

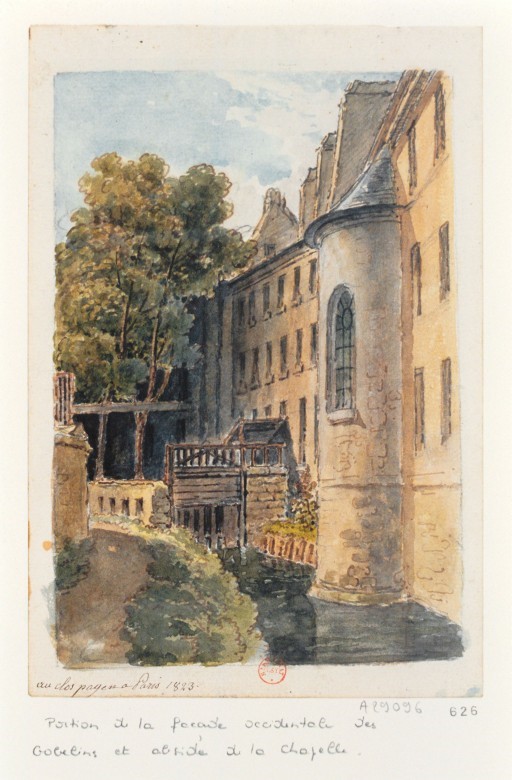

The craftsmen and their families, a total of about 200 people, lived at the Gobelins and worshipped in its chapel. Both a Catholic priest and a Protestant minister served the religious needs of the community and saw to the children’s education. In addition, there was a brewery, as the Flemish artisans preferred beer to wine.

The Manufactory, the name of which comes from the family of wool dyers already on the site, is located on the Avenue Gobelins in the 13th arrondissement of Paris. It stood next to a now-underground stream, the Bièvre, which provided the fresh water needed for dyeing – and where my murder victim’s body is discovered.

When the novel opens, Niccolò, a fictional character, is working on a pair of sculptures of Hercules and Omphale to be used as supports for the upper half of a marquetry cabinet-on-stand. The cabinet I describe is based closely on this one in the J. Paul Getty Museum. The central panel shows a rooster, the symbol of France, striding triumphant over the eagle of the Holy Roman Empire and the lion of Spain and the Netherlands, France’s enemies in the war of 1672-1678.

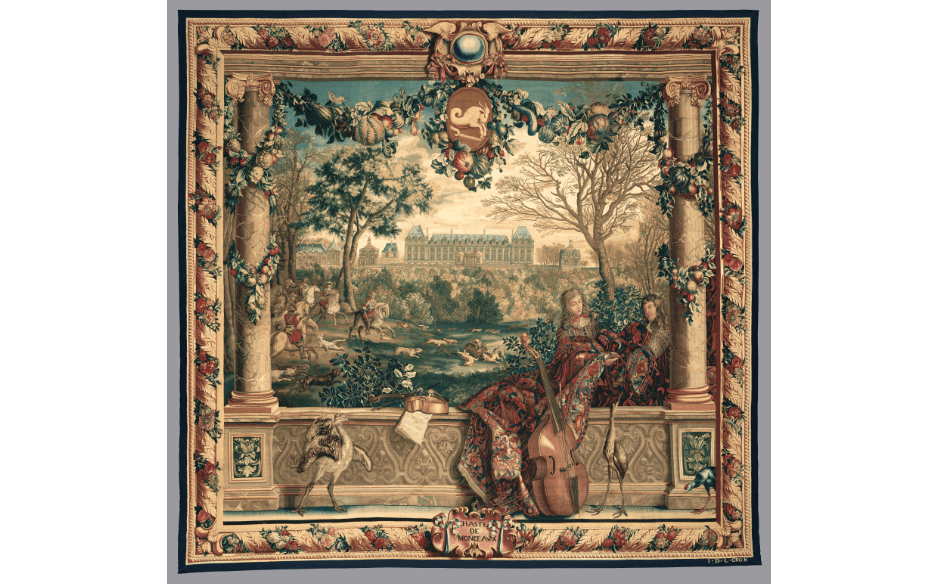

Two tapestries play a part in my novel. In one scene, the painter Saint-André (a historical figure) works on the cartoon (painted design) for Château of Monceaux / Month of December. Louis used this château, which no longer exists, as a hunting lodge. He and his companions can be seen on horseback in the middle ground, where his dogs pull down a wild boar. Royal pages hold up a magnificent carpet as birds from the King’s Menagerie at Versailles strut across the foreground.

In another scene, the Flemish weaver Willem (a fictional character) is at work on a Char de Triomphe (Triumphal Chariot), one of a series of portieres, decorative tapestries that covered doorways to keep out drafts. Its elaborate design is full of symbols of Louis XIV, including the King’s coat of arms, a blazing sun face (referring to his nickname, the Sun King), his crown and the scales of justice. The chariot, suits of armor, and battle flags celebrate his victories on the battlefield.

Willem works at an haute lisse (high warp) loom. The weaver pulls at the overhead lisses to separate the warp threads so that the bobbins around which the yarn is wrapped can be pulled through to fill in the pattern drawn on the warp threads. There were also workshops with basse lisse (low warp) looms, at which the weavers used foot treadles to separate the warp threads. Yarn made of wool was most common; silks were used to add a sheen to the colors. Gold and silver highlights were achieved by twisting thin strips of gold and silver around the yarn. I am often asked whether children took part in the weaving of tapestries, as they do in the making of Persian carpets, but this was considered arduous men’s work. Women were not employed at the Gobelins until the First World War, when the men were called away to fight.

The expense of Louis XIV’s wars that caused the silver furniture to be melted down ultimately forced the closure of the Gobelins Manufactory in 1694. When it re-opened in 1697, only the tapestry workshops remained. It shut down again during the French Revolution but re-opened to produce tapestries for Napoleon and the Bourbons of the Restoration. Carpet workshops were added in 1826. The Manufactory, at 42 avenue des Gobelins, is still active; you can visit it today to see weavers use age-old techniques to make tapestries and carpets of contemporary design.

Buy A Fine Tapestry of Murder here

Captions and photo credits:

Fig. 1. Louis XIV visiting the Gobelins on 15 October 1667. Tapestry woven at the Gobelins 1729-1734. Designed by Charles Le Brun; cartoon painted circa 1673-1677 by Simon Renard de Saint-André; woven in the atelier of Leblond. Wool, silk, and gold, 370 x 576 cm. Musée National du Château, Versailles, GMTT 98.10.

(Photo permission, www.alamy.com, $49.99 for website use)

Fig. 2. View of the Rear of the Manufactory of the Gobelins with the Apse of the Chapel, 1830. Artist unknown.

(Photo permission: Public domain)

Fig. 3. Cabinet on Stand, about 1675-1680. Attributed to André-Charles Boulle (French, 1642-1732). Oak veneered with pewter, brass, tortoise shell, horn, ebony, ivory, and wood marquetry; bronze mounts; figures of painted and gilded oak; drawers of snakewood, 229.9 × 151.2 × 66.7 cm (90 1/2 × 59 1/2 × 26 1/4 in.). Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 77.DA.1.

(Photo permission: Not copyrighted. Getty Open Content Program)

Fig. 4. Château of Monceaux / Month of December. Design conceived by Charles Le Brun , about 1665- by 1668 (French, 1619 – 1690). Cartoon for the horizontal-warp loom painted collaboratively by Joseph Yvart, (French, 1649 – 1728); Abraham Genoels (Flemish, about 1640 – 1723); Adriaen-Frans Boudewyns (called Baudoin) (Flemish, 1644 – 1711); François Bonnemer (French, 1637 – 1689); Jean-Baptiste Martin (called Martin des Batailles) (French, 1659 – 1735); and Various makers, about 1668. Royal Factory of Furniture to the Crown at the Gobelins Manufactory (French, founded 1662) in the horizontal-loom workshop of Jean de la Croix (French, died 1714) before 1712. Wool and silk, 317.5 x 330.8 cm. (125 x 130 ¼ in.). Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.DD.309

(Photo permission: Not copyrighted. Getty Open Content Program)

Fig. 5. Portiere of the Chariot of Triumph. After cartoon attributed to Beaudrin Yvart (French, 1611 – 1690) and from a design by Charles Le Brun (French, 1619 – 1690). Royal Factory of Furniture to the Crown at the Gobelins Manufactory (French, founded 1662) in the low-warp workshop of Jean de la Croix (French, died 1714) or possibly in the low-warp workshop of Jean de La Fraye (French, about 1655 – 1730, foreman of the fourth low-warp Gobelins workshop 1699 – 1730). Woven 1699-1703 or 1715-1717. Wool and silk, 357.5 × 277.8 cm (140 3/4 × 109 3/8 in.). Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 83.DD.20

(Photo permission: Not copyrighted. Getty Open Content Program)

Fig. 6. Weaver at a high warp loom

(Photo permission: Wikipedia.fr entry for Lissier. I’ve been unable to find out if it is copyrighted.)

Fig. 7. The entrance to the Gobelins Manufactory as it looks today.

(Photo permission: Public domain.)