Lady Rochford, The Real ‘Wicked Wife’ by Alison Weir

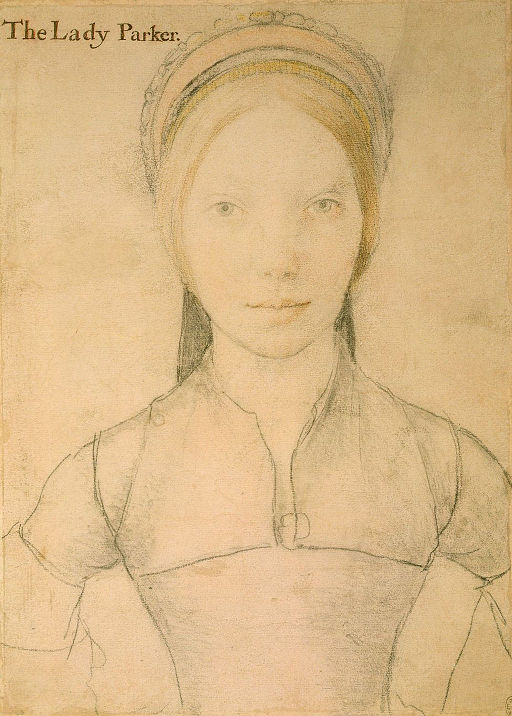

The notorious Lady Rochford was born Jane Parker, the daughter of learned Henry Parker, Lord Morley; her mother, Alice St John, was a distant cousin of King Henry VIII on his grandmother Margaret Beaufort’s side. Jane was `brought up in the court` from a ‘young age’ as a maid of honour to Katherine of Aragon. In 1520, she attended the Queen in France at ‘the Field of Cloth of Gold’, the fabled meeting between Henry VIII and Francis I. By 1522, Jane had become one of the court`s young stars. That year, she danced in the guise of ‘Constancy’ in a pageant with Anne Boleyn and other maids-of-honour.

By the end of 1524, Jane was married to George Boleyn, Anne’s brother. As a wedding gift, the King gave the couple the manor of Grimston in Norfolk. The Boleyns would soon be going up in the world, after Henry VIII began courting George`s sister Anne with a view to making her queen. In 1529, when his father Thomas Boleyn was created earl of Wiltshire, George became Viscount Rochford. By then, he was one of the most powerful men at court, loaded with offices and wealth.

Jane was a long-standing member of Anne Boleyn’s circle. She went to France in her train in 1532 and, when she became queen in 1533, served her as a lady-in-waiting. At Anne’s coronation that year, Jane was given prior place with many great ladies.

An usher of the court, George Cavendish, who knew Jane but had no love for the Boleyns, took a poor view of her. He wrote that she had been brought up without a bridle, and left to follow her lust and filthy pleasure, wasting her youth; she had no respect for her marriage vows, and did not fear God.

Jane certainly had a talent for plotting; she was to prove that again and again. In October 1534, when Henry VIII was unfaithful, Anne asked Jane to help her get rid of his mistress, whose identity is unknown. The plan was to replace her with Madge Shelton, the Queen’s cousin, for Madge was sympathetic to Anne, who thought she would not be so much of a threat to her. But Henry found out about their scheme, and Jane was dismissed from her post of lady-in-waiting and banished from court. It is not known when, or if, she returned.

In October 1535, while the King and Queen were away on a tour of the kingdom, Henry`s daughter Mary was seen in public. She was popular, and many felt sorry for the way she and her mother had been treated. To show their support, ‘a vast crowd of women, unknown to their husbands, came before her, weeping and crying that she was their true Princess’. To call her such was treason, and the ringleaders were arrested and imprisoned in the Tower. One was Lady Rochford, but she does not appear to have been confined there for long.

It seems odd that Jane, whose fortunes were bound up with the Boleyns, rallied in favour of Mary. Yet already some of their party had been alienated from them by Anne’s pride and sharp words. It may be that Jane was jealous of her husband’s close bond with his sister, so her breaking with his family makes sense.

Sir Francis Bryan was a supporter of the Lady Mary. In 1536, when he and his friends were plotting Anne’s ruin, he visited Jane`s father, Lord Morley, possibly to tell him that his daughter had accused her husband and the Queen of incest. Bryan perhaps hoped to gain the support of the shocked father for the Lady Mary. He probably knew that Morley was a friend of Mary.

In June 1536, after the executions of Anne and her brother, Morley would visit Mary with his wife and Jane. They spoke only of ‘things touching to virtue’. Morley was to praise Mary in the books he gave her in the future. When she became queen in 1553, he spoke of ‘the love and truth that I have borne to your Highness from your childhood’, revealing that he had been loyal to Mary for decades.

Jane had doubtless been influenced from an early age by her father`s love for the princess. He had held up Mary as a model of virtue and learning to his family. Having been brought up at the court of Katherine of Aragon, Jane would have known Mary well. It is easy to see why she felt a loyalty to her. Possibly she hoped to see her restored to the succession.

There was another good reason why, in 1535, Jane might have turned from the Boleyns. Lord Morley had served the King`s grandmother, the Lady Margaret Beaufort. It was in 1535 that the Lady Margaret’s great friend, John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, was beheaded for his support of Queen Katherine. Morley had been present in 1509 when Lady Margaret died during a Mass said by the Bishop. People blamed the Boleyns for Fisher`s fate, and perhaps Lord Morley and his family did too, choosing, like many others, to distance themselves from Anne Boleyn and place their hopes for the future in the Lady Mary.

But in 1536, Jane went so far as to accuse George Boleyn of incest with his sister the Queen. Some have tried to cast doubt on this, but reliable sources of the period, notably George Cavendish and George Wyatt, who got his information from his family – his grandfather, the poet Thomas Wyatt, had unsuccessfully pursued Anne Boleyn and, in 1536, had been one of those committed to the Tower on her account –

and from two ladies who had served Anne Boleyn, show that it was George’s ‘wicked wife’ who betrayed this ‘cursed secret’ and was out for his blood. What could have driven Jane to do that?

It seems their marriage was not happy. There were no children. George Boleyn, Dean of Lichfield under Elizabeth I, seems to have been Rochford’s bastard. The marriage may have failed early on. In 1526, within two years of his wedding, Rochford had acquired a book, an attack on women and wedlock, which perhaps matched his own views on his wife and their marriage. The writer dates his torments to the day he was wed.

George Boleyn had been at court since his early teens at least. He was good looking and loose in morals. Cavendish wrote that his life was ‘not chaste’, his ‘living bestial’. He ‘forced widows and maidens’, and ‘spared none at all’. Rape was bad enough, but the word ‘bestial’ might imply that he committed buggery too on his unwilling victims; Cavendish refers to Rochford being unable to resist this ‘vile’ and ‘unlawful deed’. On the scaffold, Rochford confessed that his sins were so shameful they were beyond belief, and he had known no man so evil.

Rochford may have forced Jane to submit to the kind of sex that outraged her. That would have been cause enough for her hatred. Some have said that Jane sought revenge on him after finding out that he had had gay sex with Mark Smeaton. But, if that was true, why incriminate his sister Anne? Unless, of course, Jane really believed that they were lovers. Given Rochford’s other proclivities, it was all too credible.

Jane may have been jealous of Rochford`s close bond with Anne. It was said she ‘acted more out of envy than out of love towards the King’. Perhaps Jane believed that Anne had been instrumental in sending her to the Tower. Maybe she could see that the Boleyns were on a headlong course to ruin and thought it a good idea to distance herself from them. And Thomas Cromwell, the King’s chief minister, who was in charge of the investigation that brought Anne down, might have put pressure on Jane to lay evidence against her.

Anne and Rochford went to the block in May 1536. Lady Rochford, a ‘widow in black’ with a face of woe, left court. George’s assets were seized by the Crown and given away, leaving her in penury; even her rich court gowns had been taken from her. She was forced to beg Cromwell for help. He and the King acted at once, with Henry forcing George’s unwilling father to assign her a larger income.

Soon afterwards, Lady Rochford was brought back to court as a lady in waiting to Henry’s third wife, Jane Seymour. She remained in favour and went on to serve two of his later queens, Anne of Cleves and Katheryn Howard.

But, in 1541, Jane became a party to treason. She rashly encouraged and abetted Katheryn Howard`s affair with Thomas Culpeper, helping them to meet in secret. She even let them use her own room at court. It was sheer stupidity because she was putting herself, and them, in grave danger. She has been called a meddler who got a sordid thrill from it all, and Katheryn herself would accuse Jane of having a ‘wicked’ mind.

When Katheryn’s promiscuity before marriage came to light, she was put under guard with Lady Rochford and other attendants. After the affair with Culpeper was uncovered, Jane too was arrested. When Katheryn was confined at Syon Abbey, Jane was sent to the Tower. Some of the Queen`s women revealed to the Council that she had been a party to some ruse of the Queen’s and had passed on letters to Culpeper. They described how Lady Rochford had locked the King out one night when he came to visit the Queen, and how she had kept watch for the lovers. Then a letter from the Queen to Culpeper was found. ‘Come to me when Lady Rochford be here,’ she had written.

Jane was now seen as the chief cause of the Queen’s folly. She, more than anyone, had good cause to know what became of people accused of treason. Quizzed by the council, she threw Katheryn to the wolves and said she thought Culpeper had had sex with her. She told them that the affair had begun in the spring and provided damning details. She made it clear that Katheryn knew the risks she was taking. Culpeper, in turn, accused Lady Rochford of goading him to love the Queen.

Back in her prison, ‘that bawd Lady Rochford’ was so scared of what might be done to her that she was ‘seized with raving madness’. The law did not permit mad persons to be executed, but Jane`s ‘fit of frenzy’ did not save her. The King sent his doctors to treat her, and an Act was passed enabling him to put an insane traitor to death. In January 1542, an Act of Attainder found Jane guilty of high treason, and she followed Katheryn Howard to the block on 13 February 1542. When she was brought to the scaffold, she ‘seemed to be in a kind of frenzy till she died.’ She made ‘a long discourse of several faults which she had committed in her life’ before surrendering herself to the executioner.

Jane’s head was displayed on London Bridge; the rest of her body was buried in the royal chapel of St Peter ad Vincula within the Tower. In 1876, experts excavated some of the graves in the chancel. It is almost certain that the bones reburied as ‘Lady Rochford’ were in fact Anne Boleyn’s.

Many years later, George Cavendish wrote that Lady Rochford’s ‘slander for ever shall be rife’ and that she would be called the woman who craved vice. Jane may have experienced a vicarious thrill from aiding Katheryn Howard and Culpeper, but she and Culpeper may have had another agenda entirely and hoped to enrich themselves when Henry VIII died and Katheryn, a wealthy widowed queen, was free to remarry. ‘O foul lust of luxury,’ Cavendish lamented.