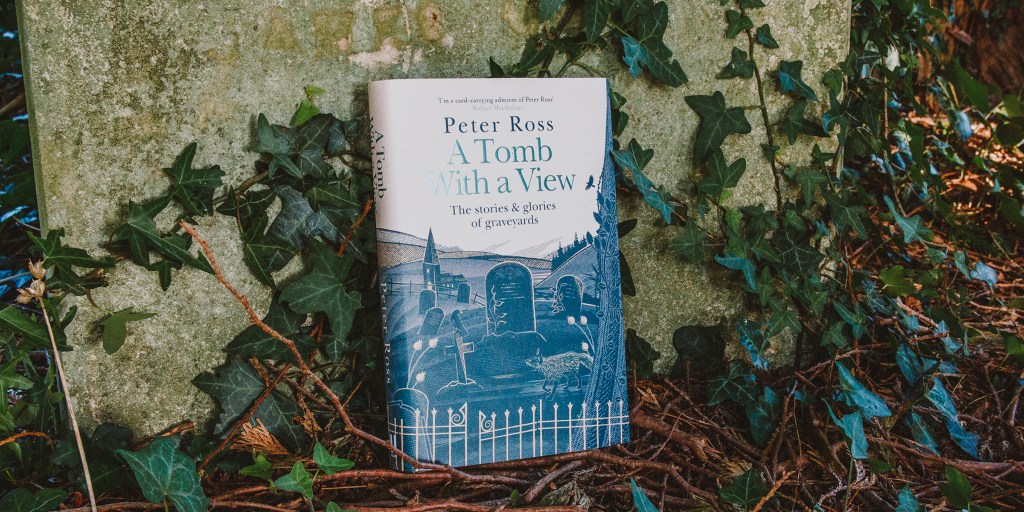

Q& A with Peter Ross, author of A TOMB WITH A VIEW

What inspired you to write A Tomb With A View?

There is a tumbledown graveyard on the hill behind my house. One day, walking in there, I chanced upon a grave, half hidden in the bushes. The inscription caught my eye: “Mark Sheridan, Comedian.” He had died, it said, in 1918. This was the English music hall star who had first sang I Do Like To Be Beside The Seaside. What was he doing buried in Glasgow, so far from the sound of the silvery sea? It struck me then that every gravestone is a story, and I set out to learn and tell as many as I could.

Did you visit many graveyards and cemeteries while working on the book?

Yes, burial grounds of all kinds from the vast Victorian cemeteries of London, those great gardens of death, to little country churchyards. Some of the people I write about, such as Karl Marx, have grand tombs that have become tourist attractions and places of pilgrimage. In many ways, though, I prefer the lesser known. Lilias Adie, a woman accused of witchcraft in the early 18th century, is buried beneath a stone slab below the tideline of the Fife coast. I had to wade out among the mud and seaweed to visit her grave. It’s a lonely spot and I was glad to pay her a visit.

What did you learn that surprised you most during your research?

I hadn’t realised that the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, the organisation that looks after those famous cemeteries with their beautiful white stones, is still kept busy recovering fallen soldiers. So many died, during the First World War in particular, that it’s common for their bodies to be found during building works, farming and so on. I went to Belgium to attend a military funeral for two British soldiers who had been exhumed from a battlefield, and being there meant I was on hand for, well, let’s just say: an extraordinary discovery.

Do you have a favourite grave or graveyard?

Oh, I love them all. I love the bones of them. But I do feel a certain fondness for the days I spent at Highgate in London. That’s not so much to do with the many famous people buried there, although it is such a treasure house of stories. What I like are the people who work or volunteer there, and who visit the graves loved ones. The gravedigger, the gardener, the stonemason, the tour guide. Highgate is full of great characters, people who are passionate about the place and work to keep it going. That, ultimately, is what my book is about: how graveyards live.

So it’s not a morbid subject?

No. There is sadness in my book, just as there is in life, but – again like life – it’s full of humour and interest and, most of all, love.

I finished this book shortly before the coronavirus lockdown, and spent a lot of that period walking in the cemetery behind my house. Some might say that it’s a little on-the-nose to visit a place like that when so many were dying, but I found it a place of solace. There was a feeling of arm-around-the-shoulder solidarity with those who had gone before. All these folk had delights and troubles of their own. They lived through world wars, through depressions economic and personal. To keep their company at a time of crisis was comforting: social distancing among the dead.

In any case, I could see that many others were doing the same. The cemetery was busier than I had ever seen it. I think the British people love a good graveyard. We don’t talk about it much, but there is a great enthusiasm for these places – their crumbling beauty and stories written in stone.

**WINNER OF THE SCOTTISH NON-FICTION BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD 2021**

**A FINANCIAL TIMES, I PAPER AND STYLIST BOOK OF THE YEAR**

'In his absorbing book about the lost and the gone, Peter Ross takes us from Flanders Fields to Milltown to Kensal Green, to melancholy islands and surprisingly lively ossuaries . . . a considered and moving book on the timely subject of how the dead are remembered, and how they go on working below the surface of our lives.' - Hilary Mantel

'Ross is a wonderfully evocative writer, deftly capturing a sense of place and history, while bringing a deep humanity to his subject. He has written a delightful book.' - The Guardian

'The pages burst with life and anecdote while also examining our relationship with remembrance.' - Financial Times (best travel books of 2020)

'Among the year's most surprising "sleeper" successes is A Tomb with a View. In a year with so much death, it may have initially seemed a hard sell, but the author's humanity has instead acted as a beacon of light in the darkness.'

- The Sunday Times

'Fascinating . . . Ross makes a likeably idiosyncratic guide and one finishes the book feeling strangely optimistic about the inevitable.' - The Observer

'Ross has written [a] lively elegy to Britain's best burial grounds.' - Evening Standard (*Best New Books of Autumn 2020*)

'One of the non-fiction books of the year.' - The i paper (*2020 Best Books for Christmas*)

'Brilliant.' - Stylist (*Best Christmas books for Christmas 2020*)

'Never has a book about death been so full of life. James Joyce and Charles Dickens would've loved it - a book that reveals much gravity in the humour and many stories in the graveyard. It also reveals Peter Ross to be among the best non-fiction writers in the country.' - Andrew O'Hagan

'His stories are always a joy.' - Ian Rankin

'I'm a card-carrying admirer of Peter Ross.' - Robert Macfarlane

'A startling, delight-filled tour of graveyards and the people who love them, dazzlingly told.' - Denise Mina

'A phenomenal, lyrical, beautiful book.' - Frank Turner

'A walk through the graveyards of Britain guided by one of the most engaging wordsmiths willing to take you by the hand.' - The Big Issue (*Best Books 2020*)

'A celebration of life and of love. It confronts our universal fate but tends towards a comforting embrace of mortality. It is also imbued with something deeply moving.' - The Herald

'Beautifully written and strangely life affirming.' - Norman Blake, Teenage Fanclub

For readers of The Salt Path, Mudlarking, Ghostland, Kathleen Jamie and Robert Macfarlane.

Enter a grave new world of fascination and delight as award-winning writer Peter Ross uncovers the stories and glories of graveyards. Who are London's outcast dead and why is David Bowie their guardian angel? What is the remarkable truth about Phoebe Hessel, who disguised herself as a man to fight alongside her sweetheart, and went on to live in the reigns of five monarchs? Why is a Bristol cemetery the perfect wedding venue for goths?

All of these sorrowful mysteries - and many more - are answered in A Tomb With A View, a book for anyone who has ever wandered through a field of crooked headstones and wondered about the lives and deaths of those who lie beneath.

So push open the rusting gate, push back the ivy, and take a look inside...