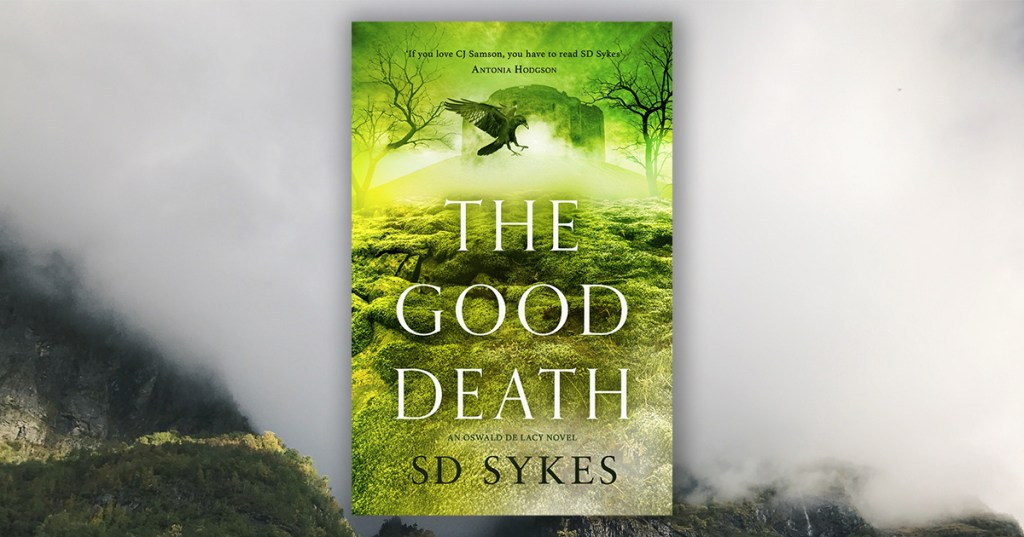

The Good Death – Extract

Kent, June 1349

It was the first hot day of summer, and I had been sent to the forest to find Sundew. Brother Peter had told me where to look – in the quaking bog near to the river, where this rare flower hid amongst the Water Mint and the Creeping Jenny. According to Peter, the Sundew attracted flies to its leaves with a sweet smelling gum. Once stuck there, the unfortunate creatures could not escape their fate – to be wrapped in the leaf and then ingested. It sounded like a strange plant to me, and it certainly grew in a strange enough place – in an open mire that was now steaming in the midday heat. I had been told to return to the monastery with a full basket of leaves, as they were needed urgently to treat one of our oldest monks – a brother with an abscess on his leg that wouldn’t heal.

My tutor Brother Peter believed that the Sundew leaves would draw out the inflammation and ease the risk of the poison spreading throughout the patient’s body – though I wondered if this were the only use Peter intended for this plant. I had also heard that it could be cooked up as a sedative. And sedation was most certainly needed in this case, for the old monk’s constant groaning was so loud that it had disturbed the Abbot – a man whose patience was notoriously short. I knew that the Abbot had personally told Peter to solve the problem, even if it meant

inducing the old monk into an almost permanent sleep.

As I tramped across the boggy ground that day, I must admit that I was feeling a little sorry for myself. The role of collecting herbs and plants in the forest had always belonged to a monk called Brother Merek. But then, about six weeks earlier, Merek had suddenly disappeared from the monastery, and somehow all of his chores had become mine. I half-wondered, as I made my way around the orange water of the bog, whether I might come across Merek’s dead body between the moss and lousewort, since his last known whereabouts were somewhere in this area. Though this thought was just my own fanciful imagination, because it was much more likely that Merek had run away with a woman. At least that’s what some of the brothers were saying.

As it turned out it wasn’t Merek who I found that day. It was somebody else. But I’ll soon come on to that.

After filling my basket with the leaves and stalks of the Sundew plant, I retreated to the trees beyond the bog, looking for somewhere to wash my hands. The Sundew was as sticky as Peter had warned, and I needed to remove the gum and unpleasant scent from my skin. Not wanting to use the dirty water in the bog, I wandered a little way between the trees, where the soil was firmer and drier, soon finding a shallow stream. It was here, as I let my hands dangle in the cold water that I heard a noise behind me – a rustling and snapping of twigs. When I turned around, I saw a small face looking out at me from between the stems of a hazel bush. I recognised her immediately. It was Agnes Wheeler, a girl who sometimes came to the monastery to take away our clothes and sheets for washing and mending.

‘What’s the matter Agnes?’ I called out. ‘What are you doing here?’

But these simple words only terrified her. That’s what I remember most. Her face was pale and panicked. Her eyes were flitting about in fear. I called out again offering my assistance, but this time she darted out from the bush and ran away from me, soon disappearing between the trees.

I only wanted to help her. That’s why I chased the girl, even though I shouldn’t have done it. The nearer I got to her, the faster she ran, until she came to the river. I thought she would stop here as it was a natural barrier. But instead she carried on, wading into the fast waters without looking back.

I shouted from the bank. ‘Agnes. Stop! It’s dangerous in there.’

She turned to speak to me at last, and I could see that her hair was tangled and her clothes were torn. ‘Keep away,’ she hissed. ‘Keep away from me, priest!’

‘But it’s me, Agnes. Brother Oswald from Kintham Abbey,’ I said, not understanding her reaction. I was only a few years older than Agnes and we had always been on good terms. I held out my hand and started to wade out, but this was my worst mistake of all. To escape me, she stepped out too far, where the water was deeper and the flow was faster. Within a flash she was washed away – her hands flailing as she vanished beneath the rapid, plunging flow.

I didn’t know what to do. Try to swim after her, or run along the banks and try to fish her out. I chose the second option, as I wasn’t a strong swimmer and my woollen habit was already heavy with water. I dragged myself out of the river, and found a path along the banks, hoping to catch sight of Agnes again. All the time, I was praying that she might have grabbed an overhead branch or clambered to safety at a shallow turn. But that’s not what happened.

I eventually found Agnes, washed up in a pool, where the waters now lapped gently at the reeds, exhausted after their furious descent from the higher ground. It was here that I dragged her from the river and laid her out in the mud, trying to drain the water from her lungs. Her limp, silent body showed no signs of life however, no matter how hard I tried to shake the air back into her. She was dead, and it was my fault. I hadn’t meant to kill her, but I had.