Ghost Ships and the End of the World by Karen Maitland

Since ancient times, the sea has meant life for coastal communities of the British Isles, providing food, salt and even driftwood for building our homes and heating them. But we always have feared the sea too, not just for its own destructive power, but for the ships that sail on it bringing bloodthirsty pirates and warriors like the Saxons and Vikings to loot, rape and slaughter. But many of these early invaders settled and their mythology became part of our folklore which continues even to this day.

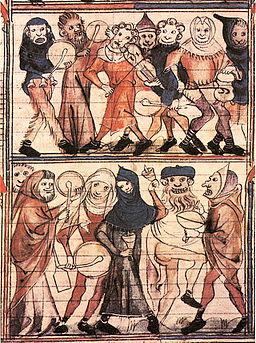

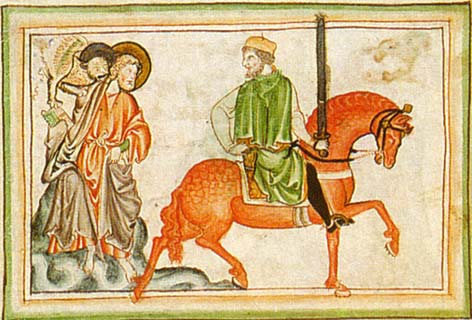

In my new medieval thriller, The Plague Charmer, we encounter a group of men and women in hiding because their leader has convinced them that the terrible plague raging across the land is proof that end of the world is coming as predicted in the ‘Book of the Revelation of St John’. This book, which can be found in the New Testament, was believed by many in the Middle Ages to be a literal account of what would happen in the end days – the sun would grow dark, the moon would turn to blood, the stars would fall from the sky and there would be terrible winds and earthquakes. Four riders on different coloured horses would gallop out across the world, each unleashing a new horror – famine, death and disease, war and judgement. They were known as the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Medieval Christians believed that the end of the world would involve a final dreadful battle between the forces of good and evil in a place called Armageddon.

But the pagan Vikings who invaded England also believed that the world would end with a terrible battle. They too predict that the stars would vanish and the land would shake, uprooting trees and tumbling mountains. The giant Midgard Serpent which lived in the sea would be so enraged that it would swim to the shore, causing a huge tidal wave that would flood the shores and cause a great ship known as ‘Naglfar’ to break free from its moorings and set sail with her blood-chilling cargo. According to Viking legend, Naglfar would carry an army of monstrous warriors to the place of the last battle. The war was so inevitable that the Naglfar was, even then, being slowly constructed. But this ship was not being built from wood like a normal warship; the Naglfar was made from the fingernails and toenails of dead men!

The enduring power of this legend may lie behind a custom which still is practised today: trimming the fingernails of a corpse before burning or burial. The Vikings were careful to do it so that the nails of the deceased could not be used to hasten the building of the ship that would bring about the end of the world. The shorter the nails of the dead, the longer it would take to build Naglfar, so the longer the world would survive.

Throughout the centuries it was thought that nail pairings, teeth and hair, anything that grew from the body, could be used in spells and curses to bring about misfortune – even death – if they fell into the hands of someone with evil intent. Therefore, nail clippings were always carefully burned or buried under a sacred tree. In Somerset, even in the early twentieth century, some people claimed the only safe way to cut nails was over an open Bible. Sailors believed that if you cut fingernails at sea when it was calm you would whip up a storm.

Celts and Gauls believed in a ship of souls, in which the spirits of the newly deceased would sail across to the Lands of the Dead, or Isles of the Blessed which, according to Procopius of Caesarea, they thought lay west of Britannia. The British Channel must have been crowded with ghostly ships filled with the dead, sailing silently past the fishing boats and cargo ships.

The Vikings often sent cremated ashes out to sea in ships to be cast into the water, and both Saxons and Vikings would sometimes bury the cremated remains of important people in symbolic ships with grave goods, such as those that were found in a Saxon ship burial at Sutton Hoo. The bodies of Viking leaders were laid in mock ships and burned along with goods, the corpses of horses and even slaves, before being buried beneath rocks and earth. Although these burnings took place on land and not at sea, as some films have depicted, the awe-inspiring image of flames clawing up into the sky from these burial ships must have seared itself on the imagination of local people who were watching these great spectacles.

It is not surprising that the legend of ghost ships was strong in the medieval mind and continues to grip our imagination today. And when ships were found drifting with a dead crew killed by disease, or thirst, or madness caused by ergot poisoning, as must have happened from time to time when so many ships and boats were at sea, this belief in a ship of ghosts was strengthened.

The sea continues to throw up strange monsters from the deep. Underwater earthquakes cause tidal waves that can bring destruction to the land without warning. Sea storms can overturn great ships and bring cliffs and buildings crashing down. Just as it was in the Middle Ages, the sea is the Angel of Life and of Death for island nations, but even now we cannot predict which face it will turn to us.

Every mam and granddam in the village had warned us to beware the ninth wave. That’s how we’d learned to count, by watching the waves. Eight waves will gently break, the ninth wave will take you. The spirits of dead children rode on that wave.

from The Plague Charmer