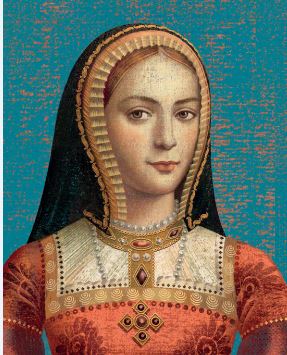

The True Queen by Alison Weir

For publication of her novel, KATHERINE OF ARAGON: THE TRUE QUEEN, in paperback Alison Weir looks at whether Katherine of Aragon was the true queen of England.

Was Katherine of Aragon right to make her stand against Henry VIII when he demanded an annulment on the grounds that their marriage was incestuous and unlawful because she had been his brother’s wife? Was she his true wife and Queen, as she insisted to her last breath?

Henry based his case on the Book of Leviticus, which warned of the severe penalty inflicted by God on a man who married his brother’s widow: ‘And if a man shall take his brother’s wife, it is an unclean thing: he hath uncovered his brother’s nakedness; they shall be childless.’ With only one daughter, and his sons all dead, Henry was as good as childless, and he was convinced that he and Katherine had offended against the law of God by their incestuous and unlawful marriage and that God, in His wrath, had denied them sons.

New evidence shows that almost certainly Katherine’s marriage to his older brother, Prince Arthur, was never consummated and, that being the case, Henry had never gone so far as to ‘uncover his brother’s nakedness’. In fact, it did not matter whether or not Katherine’s marriage to Arthur had been consummated.

An obligation was laid on the faithful by the Book of Deuteronomy: ‘Where brethren dwell together, and one of them dieth without children, the wife of the deceased shall not marry to another; but his brother shall take her, and raise up seed to his brother.’ The seemingly conflicting texts in Leviticus and Deuteronomy were the subject of much debate at the time, but for all Henry’s arguments that Deuteronomy did not apply to Christians, passages in Genesis, Ruth and Matthew give weight to it, showing that it was customary and seen as ordained by God for a man to marry his brother’s childless widow. Joseph, the earthly father of Jesus, was the offspring of such a union.

This was not incompatible with the ban in Leviticus, which actually did not apply when the brother had died childless, as Arthur had; the crucial issue was whether children had been born of the marriage. Had they been, Henry’s case would have been incontestable. This was understood by many theologians, notably the scholar Juan Luis Vives and John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, two of Katherine’s great champions. Thus Henry’s argument was flawed, whether Katherine’s marriage to Arthur had been consummated or not.

Even so, that marriage had created an affinity, or close kinship, between Katherine and Henry, which constituted an impediment to their marriage, by virtue of the fact that, by marrying Arthur, Katherine had become Henry’s sister. This was why he claimed his marriage to her was incestuous. However, such an impediment was not seen as contravening divine law, so the Pope could very properly issue a dispensation. Henry challenged this, insisting that his marriage was prohibited under divine law, in Scripture rather than by canon law, but there were many precedents, and the King’s interpretation of Leviticus, as we have seen, did not stand up to close scrutiny. It was Henry who insisted that Leviticus applied to a marriage that had been consummated, erroneously concentrating the whole focus of the case on what had actually passed between Katherine and Arthur in their marriage bed.

It was noted by Henry and his advisers that Pope Julius had not specifically removed another impediment, that of ‘public honesty’, in his dispensation of 1503. The impediment of public honesty arises from a valid but unconsummated betrothal or marriage between a man and the close blood relatives of a woman, and conversely between the woman and the blood relatives of the man, including his brother. Since public honesty exists only in canon law, and not in Scripture, the Pope could easily dispense with it. Katherine argued that, according to canon law, and precedents, the dispensation had implicitly removed the impediment of public honesty. Cardinal Wolsey wanted to press the Pope on this issue, because it might have offered Clement VII a way of annulling the marriage without offending the Emperor, but Henry was not willing, for it would have meant arguing that Katherine had emerged from her first marriage a virgin – and the Pope felt unable to accept the public honesty argument anyway.

The conclusion is inescapable: the grounds put forward by Henry VIII to secure an annulment were baseless and weak, the marriage was valid, and Katherine was the true Queen of England.

KATHERINE OF ARAGON: THE TRUE QUEEN by Alison Weir is out now in paperback