‘Take the Skull of a Hanged Man …’ – Karen Maitland

The Medieval period was an age of contradictions and none more so than the curious attitude towards the skulls of the dead. Skulls were thought to be where the human soul or spirit resided in life, and after death the skull retained the consciousness of the deceased. This belief is so ingrained in our imagination that, even to this day, if ancient skulls are discovered in houses and removed, some people fear misfortune will follow. The skull of Theophilus Brome was reported to have screamed in fury when, some centuries after his death in 1670, the tenants of Higher Chilton Farm, Somerset tried to bury it. And whenever anyone tried to remove the 300-year-old skull from Wardley Manor, Greater Manchester, the house became haunted by ghastly noises and terrible apparitions. Family members met such sudden or grisly ends that the owners were forced to produce a charter forbidding the skull to be moved.

There are known to be twenty-seven ‘screaming skulls’ recorded around Britain, including those at Bettiscombe Manor, Dorset; Burton Agnes Hall, Yorkshire; Tunstead Farm, Derbyshire and Flagg Hall, Buxton where when the master tried to take a skull from the house to a cemetery, his horse repeatedly refused to move until the skull was returned to the Hall.

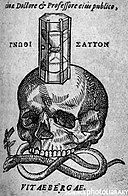

Yet, the skulls and bones of those who died on the gallows or by their own hand were not given such respect in the Middle Ages, for human bones and skulls were important ingredients in a number of cures for common ailments. In my medieval thriller, The Raven’s Head, when Gisa, the apothecary’s niece, stumbles across a skull among the herbs on the shelves of a local alchemist, she is not, at first, alarmed. After all, her uncle supplies all his ingredients.

‘That it is a human skull momentarily startles her, but it does not frighten her. On the shelves of her uncle’s shop is a jar containing the powdered skull of a suicide, a well-known cure for the falling sickness. And in another of Uncle Thomas’s small caskets are fragments of the skull of a hanged man, together with a piece of the rope used to dispatch the poor wretch. These ease the agonies of those afflicted with blinding headaches. Apothecaries regularly purchase the heads of the felons from the executioners, while the less scrupulous obtain their supply much more cheaply from the enterprising youths who steal them from the maggoty corpses in the gibbet cages. Legal or otherwise, there is always a lively trade in cadavers.’

Other uses for human skulls and bones found in medieval herbals were to mix the ashes of burnt human bones with ale to making it more intoxicating – an early example of a ‘legal high’. Red wine mixed with powdered human bones was a cure for dysentery. Gout could be relieved by applying earth together with mould scraped from leg bones removed from a grave, and headaches could be cured by taking as snuff a pinch of dried moss grown on a human skull. Even as late as 1858, a woman asked a sexton of the church at Ruabon, Wrexham, for a small piece of human skull she could grate up for her daughter who suffered from epileptic seizures.

Drinking from a human skull was a practice that predated Christianity, possibly to ensure that the wisdom, strength or courage of the dead might pass into the living. But echoes of this can be found in Christian belief. Throughout the Middle Ages it was believed that if a child was suffering from the whooping cough, he would be cured if he drank from St Teilo’s Well, Maenclochog, but only if he drank the water out of the skull of the saint.

Similarly, a belief which persisted right up until the nineteenth century was that a person could be cured of epilepsy if they drank from the skull of a man or woman who had committed suicide. It is interesting that the screaming skull of Theophilus Brome from Higher Chilton Farm was used as a drinking vessel in 1826 and old Theophilus did not seem to object, for he remained silent.

But all of the cures depended on the skull being that of an adult, for only their spirits would be strong enough to have desired effect. So when Gisa in The Raven’s Head examines the skull she has found in the alchemist’s tower, alarm bells begin to toll…

‘But Gisa can see at once this is not the skull of a hanged man, nor, she devoutly hopes, did it belong to someone who committed self-murder, for it is far too small. The owner of this little skull never lived long enough to become a man. These are the bones and skull of a young child. And the bones are fresh. They have not been dug up from some ancient grave. She has seen enough human and animal remains in her uncle’s shop to be sure of that.

How did these bones come to be in the tower? Children die of many things – fevers, starvation, accidents. Death is an all-too-common visitor to many households. But why was an innocent child not given a Christian burial or, if the poor mite was unbaptised, at least laid to rest somewhere close to a church where the shadow of the Holy Cross might fall on it? Apothecaries do not trade in the bones of children.’

Available now from Amazon and other good bookshops