Festive Tidbits from Karen Maitland

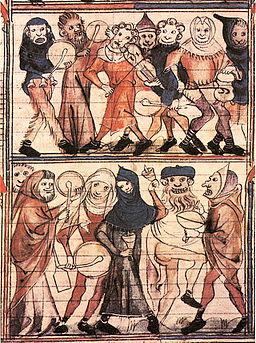

Feast of Fools

In the Middle Ages, on the eve of the Feast of Circumcision (31 December) when the Magnificat was read out in cathedrals and abbeys – He has put down the mighty – all the junior clergy would start chanting Deposuit! (Put down!). They’d drag senior clergy from their seats and take their places, appointing a fool precentor. For the next few days the ‘humble’ ruled. On 1 January, a donkey carrying a woman and baby was led into the church. At the end of the Mass, the priest brayed three times like donkey and the congregation did the same to mark Mary’s flight into Egypt.

Yule Log

The medieval yule log had its origins in the Viking Yule festival. The log had to be found, never bought, and dragged, not carried, to medieval halls. It was decorated with greenery, sprinkled with corn and ale or cider, and lit with wood from last year’s log. In Cornwall they carved a man on the old wood, a symbolic sacrifice, to ward off evil spirits. In the Highlands, a log was carved into a Cailleach Noillaich (the Christmas Old Wife). She was burned before the new yule log was lit. Yule logs had to be kept burning for the Twelve Days of Christmas.

Holly

Lincolnshire folk were nervous when taking down Christmas holly after Twelfth Night, because if it had shrivelled, it foretold a death in the family. Holly was the abode of good spirits and could only be cut at this season. It must never be brought into a home before Christmas Eve. It was said to protect houses and byres from fire, witchcraft and evil spirits, which were particularly active at this time of the year. So, holly was twisted into the circles or wreaths to hang on doors to prevent the dark forces entering.

The Devil’s Knell

On Christmas Eve in Dewsbury, Yorkshire, the Devil’s Knell is toiled on the church’s tenor bell, one chime for each year since the birth of Jesus. This is said to be a penance imposed in the thirteenth century on a member of the wealthy Saville family. He had struck and killed a servant for disobeying orders by going to Midnight Mass instead of attending his master. Saville was commanded to pay for the annual ringing of the bell which is so exhausting, it has to be done by a relay of ringers.

The Cream of the Well

Instead of queuing for the January sales, in medieval times people camped out on New Year’s Eve to be the first to draw water from a well after midnight. The ‘cream of the well’ ensured good fortune for the year. Fights broke out as people tried to get their pail in first. Hay or herbs were sprinkled in the well to thank the spirits and to warn late-comers the cream had been taken. The cream from certain wells was also said to give those that drank it the power to fly and creep through keyholes.

The Boar’s Head

Since 1340, a boar’s head has been eaten at a Christmas feast in Queen’s College, Oxford. A stained-glass window in Horspath Church tells the story. An Oxford student was walking on Shotover Hill when he was attacked by a wild boar. His only weapon was a book of Aristotle, which he stuffed down the boar’s throat, choking it. He dragged the boar back to Oxford for a feast, so beginning the tradition. Great story, but since a boar’s head had been the centre piece of the winter festival since Celtic and Viking times, the feast was probably instituted before the legend.

Dumb-cake

On Christmas Eve, unwed girls would make a dumb-cake, which included some nasty ingredient such as eggshell or soot. She’d prick her name in it and bake it, all to be done in silence with the door open. Some traditions said she should lay it on the hearth and at midnight the spirit of the person who held the key to her future happiness would walk in. Other versions said that she must put the cake under her pillow and the ghost of her future lover would appear, drawn by the smell.

Bloody Boxing Day

We know that people were regularly ‘bled’ for their health in the Middle Ages but, for centuries, valuable livestock was also bled once a year. On St Stephen’s Day (Boxing Day) horses and cattle were pierced in the neck and bled to maintain their strength. If you bleed your nag on St Stephen’s Day, he’ll work your work for ever and aye. The upside was the animals were then rested and given extra food until St Distaff’s Day (7 January) when work resumed for humans, horses and oxen after the Twelve Days of Christmas.

A Christmas Caudle

A popular medieval dish at this time of year was a warming caudle, which was thought to be nourishing and good for the stomach. There were many versions but a typical recipe was to mix honey, saffron and breadcrumbs with a ‘goodly measure’ of sweetish wine or ale, bring to the boil, and stir in beaten egg yolks to thicken. Sprinkle with sugar, ginger and a little salt and serve.

Karen Maitland is the author of THE PLAGUE CHARMER and other novels