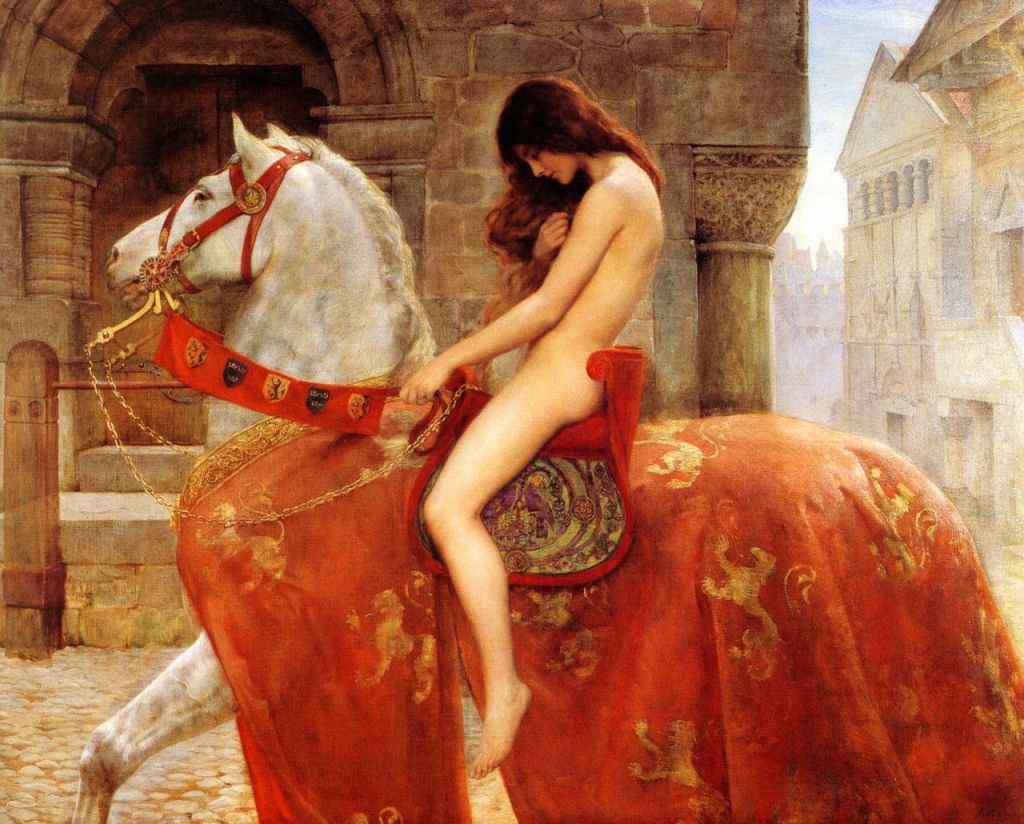

Lady Godiva by David Churchill

One of the delights of writing the Leopards of Normandy series has been the entirely unexpected discoveries that I’ve bumped into along the way. I had no idea, for example, that the Lady Godiva, who, famously, though perhaps not factually, rode naked through the streets of Coventry, was actually a Saxon noblewoman called Godgifu, whose life overlapped with that of William the Conqueror.

I was equally unaware that the Coventry through which she allegedly rode was not the bustling medieval cathedral city portrayed in most paintings of the event. In fact, it was a mere village clustered around a Benedictine monastery that contained an abbot and twenty-four monks and stood on the site of an early convent that had been destroyed by Danish raiders.

Still, Godiva and her husband, Leofric of Mercia, were the benefactors who paid for the monastery’s establishment, so their links to Coventry are well established (both, indeed, are said to have been buried in the abbey’s church). So too is the quality of Godiva’s character.

The role of women as wealthy individuals in their own right who became significant benefactors, scholars and philanthropists is a subject worthy of a blog of its own, but suffice it for now to say that Godiva was as generous as she was devout. In fact, her various gifts to religious orders and institutions were the reason for her fame in her own lifetime, and the era immediately following it.

The first known account of the Godiva legend as we know it occurs in an early thirteenth century chronicle called the Flores Historiarum (Flowers of History), written by a monk named Roger of Wendover. In his account, Godiva pleads repeatedly with Leofric to ease the burden of taxation on the people of Coventry. At last, weary of the ear-bashing, he replies that he will cut taxes if she agrees to strip naked and ride on horseback through the streets of the town.

Amazingly, Godiva agrees, on the proviso that the townsfolk all stay indoors with their windows shuttered so that none see her go by. On the day, however, one tailor called Thomas cannot resist the temptation to look so he drills a hole in his shutters to peer through: hence the expression ‘Peeping Tom’.

From a historical point of view, the story seems, at best, an exaggeration. There were probably no more than fifty households in Coventry in the 1050s, when the event is supposed to have occurred, so the treatment of those few people is unlikely to have greatly concerned an earl, or his wife, who controlled a great swathe of the English midlands. And there is unlikely to have been more than a single muddy track through the village, rather than the teeming streets of legend.

Of course, details like that are no concern to someone who is writing fiction. We novelists have other priorities.

DEVIL and DUKE by David Churchill are out now