Using Real Historical Characters in Fiction – S.G MacLean

I am often asked about the extent to which I use real historical characters in my fiction. Because I write historical crime, I don’t feel I can use real characters as the victims or perpetrators of crimes that never actually happened, so I tend to just have them as subsidiary characters, and will occasionally throw suspicion on them. However, my most firm rule is not to show real historical characters in a bad light unless the portrayal is supported by historical record. I always bear in mind that I am writing about someone who was once a living human being, and who is no longer able to answer back.

In my first historical crime series, the Alexander Seaton novels set mainly in 1620s and 30s Scotland, I only had a handful of real historical characters; Alexander was a teacher in a Northern Scottish burgh, and lived his life far from the centre of power, and while some of the real historical characters who appear in those books might have been household names in their own day – e.g. the painter George Jamesone or the cartographer Robert Gordon of Straloch, they are now largely forgotten, other than by special interest groups.

In the Damian Seeker books it is different: Seeker operates very close to the centre of power in Commonwealth England, thus inviting several very well-known names in to the story. There is Cromwell himself, of course (of whom more later), but there were several individuals working out of his Whitehall who are now better known to us for other things, and it is that that makes the Seeker books so much fun to write: I try as far as possible not to write with the benefit of hindsight, but as if I too am in the thick of things, as my characters experienced them.

For instance, a key character in The Black Friar is the poet Andrew Marvell. In 1655 Marvell, a clergyman’s son from Hull, was a tutor to well-connected children and an aspiring civil servant in Whitehall. Despite the support of John Milton, he was not particularly successful in his hopes of preferment, losing out to men whose names are now forgotten, and he does not seem to have been a particularly successful intelligence operative either. Not a natural orator, he seems to have lacked the ability to negotiate his way smoothly through the requisite social circles. The magnificently aggrieved-looking character looking out from the front cover of Nigel Smith’s biography of the poet was the key to my portrayal of him in the book. Neither Marvell, nor those around him as he struggled to get on in Whitehall, could have known then that centuries later, he would be acknowledged as one of the greatest poets of the English language.

A contemporary of Marvell’s in Cromwell’s Whitehall was Samuel Pepys, a young treasury clerk working for the duplicitous George Downing (after whom Downing Street is named). Pepys’s Diaries are a gift for any novelist of the period, and they are brought wonderfully to life in Kenneth Brannagh’s superb reading for Hodder Headline audio books. Pepys is a wonderful character to use when a little humour or human warmth is required, and he was very little effort to write.

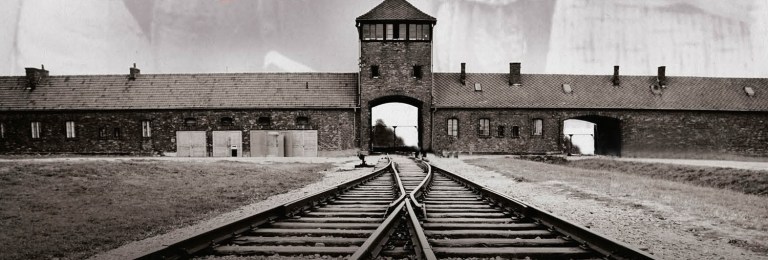

I had expected to have to take a great deal more effort with Oliver Cromwell than was eventually necessary. Before I started work on the Seeker books, I didn’t know a great deal about Cromwell, but, as a Scot of Irish descent, what I did know, I didn’t much like. I am not alone in this – the portrait of Cromwell in Inverness art gallery hangs upside down. I have to say, some fairly extensive reading didn’t much improve my personal opinion, but I have to acknowledge his military genius and his charisma. It was the charisma that I tapped in to while writing his character, for while I might not like Cromwell, Damian Seeker and others in the books – the old coffee man Samuel Kent, for instance – love him, and would do practically anything to protect the General who had led them. So, despite my apprehension, Oliver Cromwell was one of the easiest characters in the books to write in the end, seeming to take control of the keyboard as I typed. Perhaps, against my will, I too have fallen under the spell of his charisma.

Working on the Seeker books has very much softened my attitude towards using real characters in fiction – I have always been uncomfortable with the notion of making real people say and do things they might never have said or done – but the opportunity to introduce myself to some of these fascinating individuals through my books has proved something too hard to resist.