Author David Morrell on escaping to Victorian London

For the past seven years, I’ve been a time traveller, writing a Victorian mystery trilogy about 1850’s London. The three novels (Murder As a Fine Art, Inspector of the Dead, and Ruler of the Night) feature a controversial literary figure from the era, Thomas De Quincey, who was notorious for having written the first book about drug addiction, Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821), and who praised mass murderers in his famous essay, ‘On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts’.

Seven years ago, De Quincey came to my attention as I watched a film called Creation, about Charles Darwin’s nervous breakdown after the death of his favorite daughter. Darwin suffered from headaches, insomnia, heart palpitations, stomach pains, rashes, and a host of other infirmities that baffled 1850’s physicians, who couldn’t identify a disease that combined all those symptoms. The problem, of course, was psychological, not physical, but in a pre-Freud world, few people could have conceived of that idea.

Except Thomas De Quincey. At the film’s climax, a character tells Darwin, ‘There are people like De Quincey who believe that we can be controlled by thoughts and emotions we don’t know we have.’ Amazed that someone might have anticipated Freud, I set out to learn about De Quincey and discovered that he’d invented the term ‘subconscious’ and believed the human mind to have ‘chasms and sunless abysses, depths below depths’ in which there are secret chambers where alien natures can hide undetected.

The reason I watched a film about Darwin’s grief for his daughter is that dead children were on my mind. My 14-year-old granddaughter, Natalie, had recently died from a rare bone cancer known as Ewing’s sarcoma. The disease had also killed my fifteen-year-old son, Matthew. Only a couple of hundred people are stricken with it each year. It’s not believed to be inherited.

Desperately needing a distraction, I decided to write three novels in which Thomas De Quincey would explain his theories about the subconscious to Scotland Yard detectives, who proudly considered modern crime fighting to be exemplified by plaster casts of footprints. De Quincey would serve as a forerunner not only of Freud but also of Sherlock Holmes (Conan Doyle was influenced by him). But De Quincey would also be my guide as I tried to escape from my emotions.

I was determined to convince myself that I was in 1850s London. For the next several years, the only books I read were related to De Quincey and the mid-Victorian era. Literally, those were the only books I read. I acquired a large map of 1850s London and taught myself to move within it as if I were a long-ago resident. I traveled to London and roamed streets that De Quincey had written about. I went to Manchester, where De Quincey was born and where I was invited to speak about De Quincey. I journeyed to Grasmere in the Lake District where De Quincey had moved into Dove Cottage after his literary idol William Wordsworth moved out.

For seven years, I believed I was actually there, and my goal became to convince readers that they too were there. How much did a woman’s clothes weigh? What was Wyld’s Monster Globe? What was an ascending douche? The revealing answers to these and similar questions made readers understand the Victorian era in a totally new way. When Entertainment Weekly said, ‘You’ll hear the hooves clattering on cobblestones, the racket of dustmen, and the shrill call of vendors,’ I was never more gratified by a review.

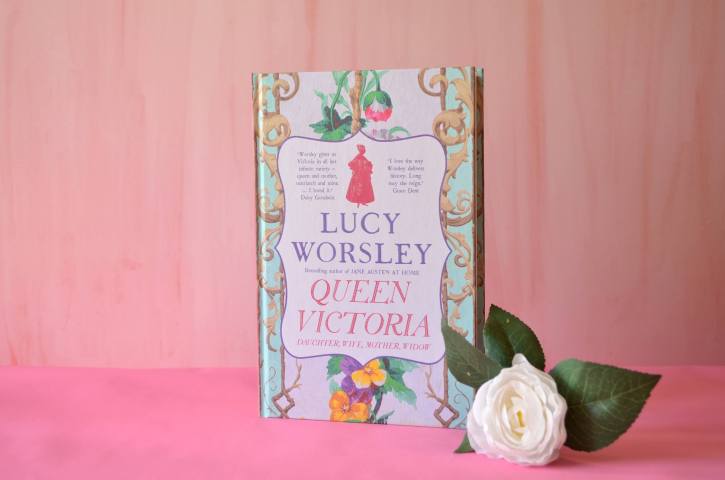

Ruler of the Night by David Morrell is published today.